|

CHAPTER 7 Dance Notation Comes Into Its Own Benesh Notation, conceived by Rudolph and Joan Benesh, was proportedly easier to read and write than Labanotation. Moreover,The Royal Ballet already employed a person trained in Benesh plus European companies were waiting to hire more as soon as they were available. The Benesh couple had created the Institute Of Choreology to fill this need. Could I help fill this need? I wondered. To stay in England was my main purpose but my work permit as a “foreign artist’ (not at all easy to acquire in the first place), was about to expire. I figured if I joined the newly opened Institute it could not only be a way to stay in England but also a chance to enter what seemed to me an exciting new profession. As soon as I returned to London I made a hasty visit to the Institute in Barons Court and met Rudolph and Joan Benesh.

I was given a basic reader of the notation to take home and study.

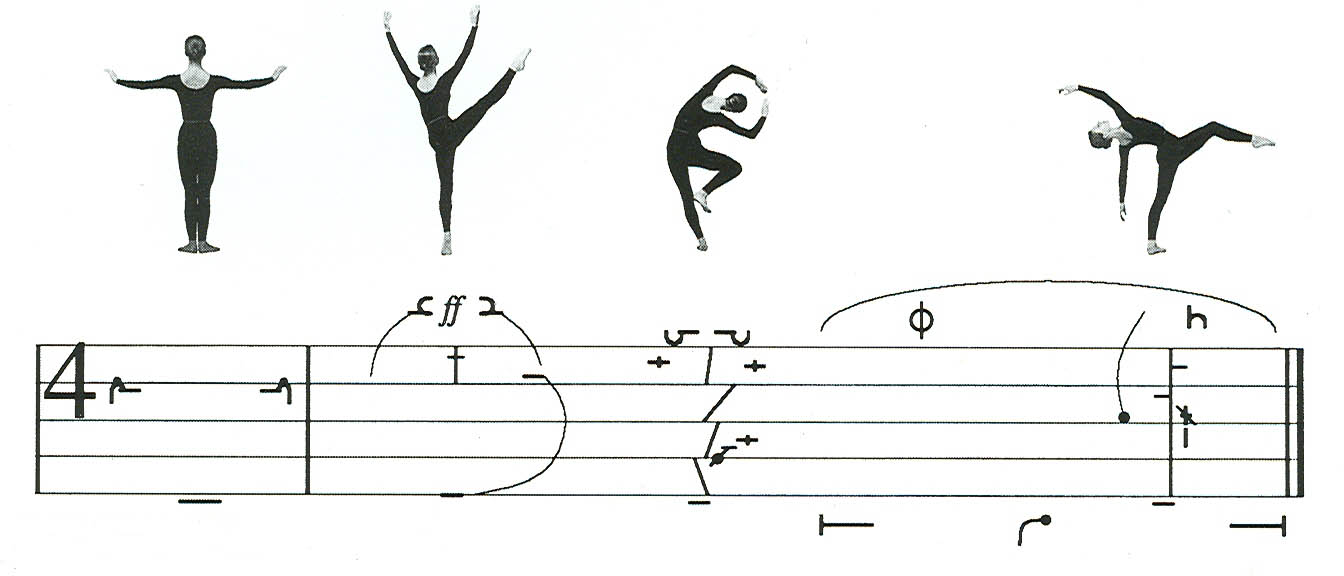

It showed how elementary positions of the body were notated, then

movements, exercises and class combinations set to various rhythms

Already having a rudimentary knowledge of Labanotation I was

familiar with the concept of recording movement on paper so within

an hour I was able to grasp the basic theory and to read through the

entire Grade One book. I could hardly wait until the following

morning to return to Barons Court. Joan Benesh held up the first

reader before my eyes and was delighted to see I could easily sight

read and execute the written positions and movements. Apparently, I

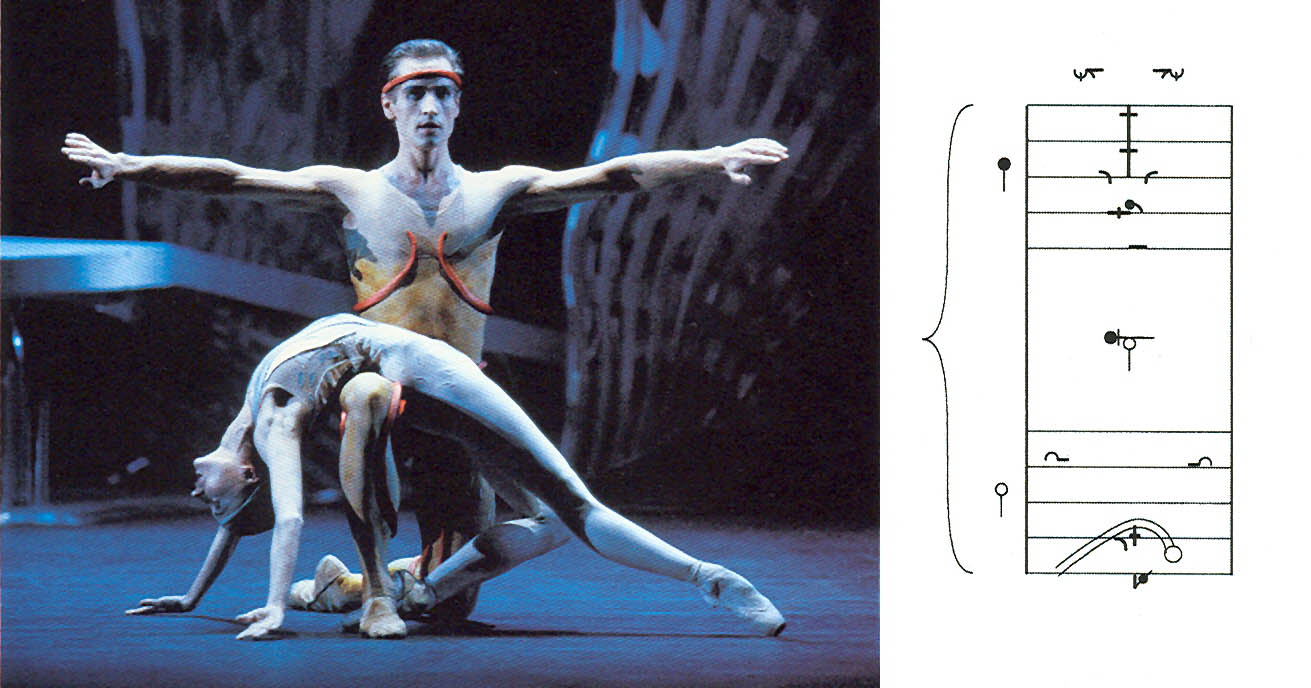

took to it quite naturally. These photographs of a dancer are written in Benesh on the staff below. The notation includes directions the body is facing, details of hands and wrists, head, torso, turning, along with timing and dynamics. In my time, choreologists notated everything by hand with computers still belonging somewhere in the future. Now, the Benesh Notation Editor (MacBenesh) comes with PC software.

I was invited to join the Institute right away. There were five others, all young ladies and I the only male. My London nightlife added to the distractions. This was during the mid-sixties. London was then known as ‘swinging London’. Fashions for the young had quickly changed, some bordering on the outrageous. Colorful flair-bottom trousers, platform shoes, fringe jackets, long hair and the Beatles were everywhere. I let my own hair grow quite long and certainly liked the platform shoes that made me appear a bit taller. One of the students was sent by John Cranko of the Stuttgart Ballet to return after finishing the course as his company choreologist. Another was from Denmark. The others were British. I was the only American. To tell the truth - apart from Mr. and Mrs. Benesh and fellow students - the Institute staff of young ladies were for the most part, arrogant, discriminatory, clearly to be disdainful of all Americans and I must add, sexist. I don’t know how often I was told my other male choreologists how they were belittled by female choreologists as not making the grade. It’s true that dance notation is a female dominated profession; yet, the two major systems were invented by men, not to mention music notation. Composers of music write everything in notation so to say that the act of writing dance movement legibly and professionally really belongs to only one sex, is, well, sexist.

To get to Barons Court from Swiss Cottage took nearly an hour on the

underground. If I left at eight in the morning, I arrived at the

Institute in time for the first class, usually ballet or modern.

Classes in music, art, anatomy, kinesiology followed, and of course

the notation theory that filled the afternoon. During the week we

had extra classes with guest teachers in Historical dance (Wendy

Hilton), Indian Dance (Marianne Balchin), Choreography (Kathleen

Russell) and a wonderful teacher of Russian Character (Anatoly

Borzoff). This small building in Barons Court was the first that housed the Institute. Offices were on the first floor. A tiny basement studio served for dance classes and the top floor was for notation theory, anatomy, music, drawing and a library of the already finished scores. The Royal Ballet Upper School and rehearsal studios were then just across the tracks on the other side of Barons Court station. We could look out our windows and watch rehearsals going on and even had the use of their cafeteria. Going there for lunch there was always the chance to mix with the Royal Ballet dancers and occasionally its stars, at that time Nureyev, Fonteyn, Sibley, Dowell, and sometimes even Sir Frederic Ashton or Dame Ninette de Valois, the founder of the Royal Ballet. This Upper School finally moved in 2003 to Floral Street, alongside the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, fulfilling Madam’s dream to have a Company and School side by side in the center of London. During the year we each had to teach some notation classes at White Lodge, the Royal Ballet lower school in Richmond Park. I may have been the first to teach an American jazz dance class along with its notation to future members of the Royal Ballet. After I graduated, the Institute had many other locations eventually becoming part of the Royal Academy. A dance company having a notator on staff had been proven invaluable, not only to save rehearsal time but to document works for future revivals. Dance companies all over the world could now stage the works of choreographers like Sir Frederic Ashton or Antony Tudor, simply by having the notator, called a “choreologist”, travel to teach the work by means of his or her own, or even another choreologist’s written score. This new profession was also an opportunity for dancers to take on after retiring.

One evening at Covent Garden I saw the premiere of Sir Frederic

Ashton’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream”, which he called simply, “The

Dream”.

Anthony Dowell was making his

debut as Oberon. Sitting in the cheap seats and seeing the intricate

patterns of the corps dancers on the stage below, I began to wonder

how on earth could such a work be notated. I had no idea that in

only a few years time I would be teaching this entire 50 minute work

to the Joffrey Ballet company in New York, from the notated score

that the Royal Ballet choreologist had done. Back in New York they had just completed building the gigantic Lincoln Center complex with the new Metropolitan Opera as its main focus. The old Met, where as a teenager I had taken classes and was a supernumerary in the operas, had just been torn down.

Dame Alicia Markova was the ballet director. She had danced with the Diaghilev Ballet in her youth and was known the world over as the first British Prima Ballerina. When she retired she took over the ballet at the Met. I thought perhaps she would be interested in having a choreologist on staff so I decided to write her a letter. She answered that she would be in London in July and would see me then. The fact that I was in her native England may have had something to do with her quick response. So, on a hot June day Dame Alicia arrived at the Institute by taxi and watched me dance a solo from “Napoli” on the sloping, cement floor. She asked if I was Canadian. Being American and not Canadian meant I would not need working papers. That was a plus as well as a hint she was interested in hiring me. I graduated with honors and to get myself in shape in case I was called to New York - I began daily classes at the London Dance Center near Covent Garden and took a stroll every evening on Primrose Hill while dreaming of returning to America as Lincoln Center’s official choreologist. Oh, the glamour of it!

A Metropolitan Opera Contract – At Last! So, what happened to my career as a choreologist? The thing was, basically, I still considered myself a dancer and at the heart of it, didn’t mind dancing for a few more years. As it turned out, I danced for many more years in one situation or another! Antony And Cleopatra

Samuel Barber’s music for the ballet must have been a hurry up job (and sounded it) as it didn’t arrive until two weeks before opening night. His entire opera had what we all thought was the worst music we had ever heard and it was roundly rejected by many critics! Franco Zeffirelli created a production so overstocked with scenery that it broke the stage's brand new turntable during a dress rehearsal, creating a logistical mess for the other operas that season. I was on it when this happened, posed center stage on what I think was the bow of a ship. The stage was covered with gold lame. One morning, as the turn-table started to rotate, I watched in horror as the gold lame - which probably cost many thousands - began to crumple and tear. Leontyne Price was the Cleopatra. Her entrance was from the inside of a pyramid. On opening night the pyramid got stuck and she was trapped inside! She would wisely never get in it again. The choreographer, Alvin Ailey, was surely not inspired when he took on this job. In the ridiculous ballet which took place on the deck of a ship, I had to first run on-stage and set down a pot of some kind in center stage, (why and what this was for I never found out) then run to stage left, pick up two sticks and hop on a movable railroad track device that took me back on stage to join the other dancers and beat sticks on the floor in intricate rhythms which seemed to be the main focus of the choreography.

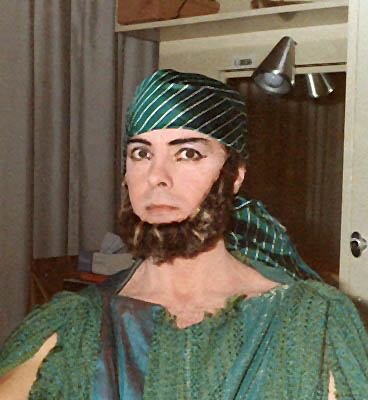

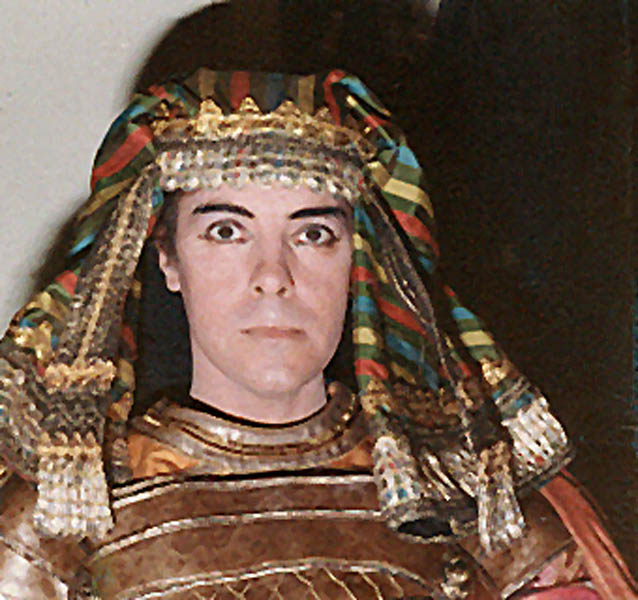

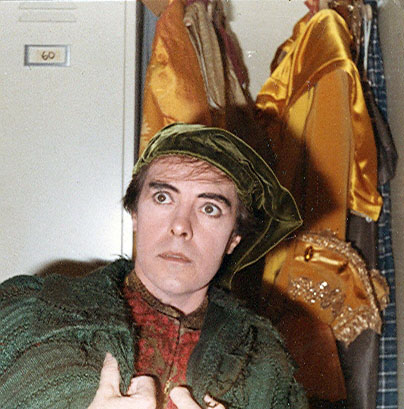

Photo: Dressing table shots of me in costumes for “Antony And Cleopatra” The weighty costumes were heavy and clumsy, but highly theatrical. This opera was to be the big showcase for the new Met. It cost somewhere in the millions. It was an extraordinary flop and was only given five performances, then never heard of again at the Met.

Photo Left: As an Ethiopian dancer in "Aida" Other operas I danced in were “Turandot”, “Faust”, “La Traviata” and as soloist in “Un Ballo en Maschera” (The Masked Ball). Being my first solo on the Met stage, I naturally wanted to make a good impression. Standing in the wings, ready to make my entrance, I suddenly realized I was not wearing the white gloves that went with the costume. Without them it would be perfectly noticeable and ruin the fine impression I wanted to make. Every dancer can relate to this. I decided to risk it, dashing up to the 3rd floor to get them from my dressing table. Returning to the main stage, breathless, horror of horrors, the chorus was just getting into place for the scene. Chorus singers never move with any kind of grace or haste. I nearly pushed some down as I scrambled to get to the center stage platform just as the curtain was being raised on the full house of 4,000 people. My partner for this pas had been terrified that I wasn’t even going to show up. So, I made a good enough start as a Met dancer but a disaster was soon to occur. Half way through the season I began to feel something was not right with my health and eventually was put me in hospital. It was a severe case of hepatitis and I literally died for a minute or so before a team of frantic doctors brought me back to life. Hepatitis was infecting a lot of people during the sixties. It was a mystery how I contacted it but a few others at the Met also came down with it, including Zachary Solov! I remained in hospital for four months. Dame Alicia or the ballet mistress, Audrey Keane, called me nearly every day.

I was released just in time to go on the Met’s National Spring tour.

Principals, singing chorus, ballet, orchestra members and management

all traveled together in the Met’s own trains. We performed in six

major cities, a week each, then overnight sleepers to the next city.

(The Met no longer does this). Photo: Dame Alicia looks on as I check my score during a rehearsal of ‘Adrienna LeCouvreur” in a subterranean dance studio at the Met. Dancers Patricia Heyes and Ivan Allen in background |

massive

scenery was designed and constructed for this premiere opera,

specially written for the occasion. Hundreds of supers, even all

kinds of animals were hired.

massive

scenery was designed and constructed for this premiere opera,

specially written for the occasion. Hundreds of supers, even all

kinds of animals were hired.

that

he really wanted to continue as the Met’s ballet director instead of

Dame Alicia, and felt that anything she did, such as hiring me all

the way from England, was wrong. Or perhaps he just didn’t like me

or felt I was too old. In any case, I only did one performance then

dropped out of it and besides, Margarita Wallman, the bad-tempered,

hyperrealistic stager of this new production, afterwards snarled at

me and said I was horrible in it.

that

he really wanted to continue as the Met’s ballet director instead of

Dame Alicia, and felt that anything she did, such as hiring me all

the way from England, was wrong. Or perhaps he just didn’t like me

or felt I was too old. In any case, I only did one performance then

dropped out of it and besides, Margarita Wallman, the bad-tempered,

hyperrealistic stager of this new production, afterwards snarled at

me and said I was horrible in it.