|

CHAPTER 11 Leningrad Why did the taxi driver single me out to be last, and take me to this hotel instead of to the more fancy, upscale “Europe” hotel on Pushkin Square where the others were taken, even the two ill-bred teenagers who had shared my ship bunk? Was it because I was alone and possibly would give an American tip in cash? Soviet law did forbid the act of tipping, but taxi drivers, and others, accepted it all the same, especially from Americans, well known as over-tippers.

Photo: The Octiabrskaya Hotel, Leningrad You couldn’t shut it off either but you could at least turn down the volume. I didn’t mind as I took it as an opportunity to learn more of the Russian language. There were wonderful afternoon radio shows for children, very much like the ones I listened to as a boy; Dick Tracy, Captain Midnight, The Lone Ranger, but these were mainly stories about children participating in the October Revolution of 1917 and a fascinating one about a girl and a friendly robot in Mongolia that I found especially interesting. This was 1969. The Soviet period was at its peak and Leonid Brezhnev still in power. The door to my utilitarian room had a large and heavy key. Each time I went in or out I had to pay a visit to the ‘dvornaya’ [lady caretaker] who sat unbudging at her desk. There was one on every floor. My phone rang constantly with Soviet citizens searching for their visiting friends. I don’t know why I didn’t just find a small apartment by myself. The hotel restaurant where I took all my meals was not to be believed. Any table I sat at turned out to be the wrong one, the ‘right’ one always rudely pointed out by an officious waiter along with mumbled curses. I could only guess it had something to do with assigned sections. Then there was the even more disagreeable service. A friendly Canadian lady who often sat at my table and who spoke far better Russian than I, made continuous complaints about the service but it was all to no avail. The food had every other foreign guest complaining but I didn’t mind the food at all. I happen to like black bread, beets and cabbage. It was then the time of ‘Byeliye Nochi” [the White Nights] a period when it never really gets dark. From my hotel window I could watch young lovers walking hand in hand at any hour of the night and I was immediately struck by the beauty of this old city.

Photo:

Nevsky Prospect, the city’s famous main street, running from the

square to the Neva river and the Hermitage Museum, formally the

Imperial Palace.

Strangely, Volodya seemed to have plenty of time to show me around Leningrad. I really don’t know why he latched on to me. At first he thought I was Italian as I was carrying an Alitalia flight bag. In a way I felt a bit lucky to have a guide and someone to practice Russian with. He was never allowed into my hotel as for some reason it was off limits for him. I had to meet him outside, and out of courtesy as I would often rather be alone. He also had a lot of friends. They usually hung out on the Nevsky Prospect at “Gostiny Dvor”, (which means literally; The Guest Yard) but it was a poor Soviet idea of a Mall. It is still there but now very chic and expensive. He introduced me to some of these friends who also knew not a bit of English except the word “Sachmo”, meaning; did I know Louis Armstrong, the American black singer who they must have heard on records. I got lost several times on my own by wandering and taking trains outside the city but there was always someone who would kindly give me directions, or even personally escort me back to my hotel. Soviet citizens were very kind and hospitable.

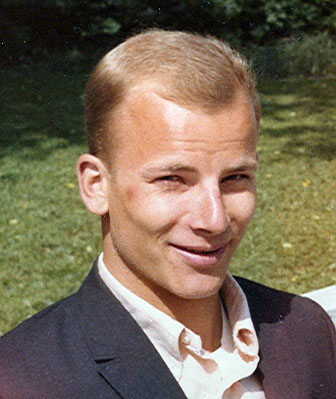

More Shady Characters During intermission I ran into John Barker, a ballet teacher in New York and an authority on Soviet (Vaganova) ballet style. He taught it in a strict, unyielding way and had translated several books on the technique. Then two overly friendly female prostitutes approached me in the lobby. At first I thought they were dancers until they coyly suggested a meeting later on and asked if I had a car, but I wasn’t in any mood for such dangerous assignations. The Kirov Theater (now back to its original name, the Maryinsky) was closed for repairs during that period. The company, both opera and ballet, were instead switched over to the “Lensoviet” theater, located quite a distance away. There I was able to see a ghastly production of “La Bayadere” and the opera “Boris Godunov” that was beyond the pale. During my stay I was able to take some classes with Anatole Borzoff, a former dancer with Moiseyev’s company and so was able to notate some of the Moiseyev technique.. To be perfectly honest, when it was time to leave Leningrad I felt a little relieved. It had been as if on a distant planet. I said my goodbyes and left presents. Volodya seemed to like American cigarettes so I gave him several cartons I bought in the Beryozka [foreign currency] shops plus a pair of jeans and some men’s cologne. He gave me a small porcelain figure of Popov, the Soviet clown that I still have to this day. For myself I bought several record albums and a balalaika [a Russian musical folk instrument]. Little did I know then that the balalaika would become so very much a part of my life in years to come. Leaving the Soviet Union was nearly as bad as entering, when my Russian language tapes were highly suspect at customs. Just as I was to board the ship back to London, the officials investigating my luggage came across my notation of folk dances and it caused quite a stir. Puzzled by the strange symbols, they seemed to think I'd been notating troop movements, or was up to some other suspicious activity. Just as they were about to seize them, I explained the only way I could; by demonstrating a few dance steps, right in front of them. Because the Russian people are so fond of dancing, and especially their own national dances, their suspicions suddenly disappeared. I boarded the ship amidst their laughter and cheers. The ship left for England, not

the Nadezhda Krupskaya this time, but the Maria Ulyanova, another

Soviet hero. A few days in London then back to New York. The Met was

still on strike. There was still the Tucson Nutcracker to do in

November but I had to make a living. There always were regional

ballet companies where I could stage productions or be a guest

teacher. I did engagements in San Francisco, Tampa, Birmingham,

Detroit and others, then by surprise, a telegram arrived from the

Institute in London. The Harkness Ballet was looking for a

choreologist and I should get in touch with them immediately if I

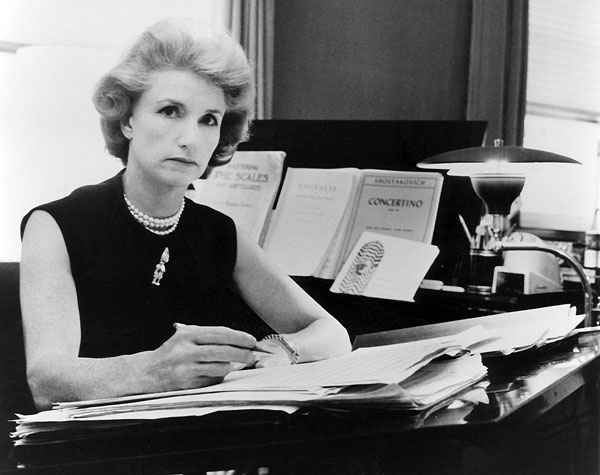

wanted the job. Rebekah Harkness was the Standard Oil heiress whose enormous wealth and eccentricity dazzled New York. She spent millions on the arts, mostly through her own dance company, the Harkness Ballet. Here was a woman who had everything. Her town house just off Central Park was where she had her school and where the company rehearsed. It rivaled the splendor of the great royal ballet schools of Europe. A magnificent entrance foyer with crystal chandeliers, a marble circular staircase, no less than five beautifully and richly decorated dance studios, offices, a library, a resident masseur and a doctor on the top floor. A bejeweled golden urn designed by Salvador Dali was on display in the foyer. (This urn was to one day hold her ashes). I was entering a palace. She had just fired her company while they were touring Europe and was starting a new one, using the trainees as replacements. The whole place was in turmoil. These young trainees were certainly a lucky bunch in my opinion. Not only did they receive free dance training but medical and therapeutic aid plus a small weekly salary to live on. Nothing even remotely like that existed during my own struggling student days. She also had just fired the two directors, (Benjamin Harkavy and Lawrence Rhodes), and hired a new one, Renzo Raiss. Being German and familiar with European ballet companies, it was really he who wanted a choreologist, along with many other changes he was making.  After

the interview he took me to meet Mrs. Harkness in her salon on the

fourth floor. She was cordial and talked about her musical training.

She liked to consider herself a composer as well as a dancer and had

studied orchestration with the famous Nadia Boulanger in Paris.

Before I knew it I was hired. After

the interview he took me to meet Mrs. Harkness in her salon on the

fourth floor. She was cordial and talked about her musical training.

She liked to consider herself a composer as well as a dancer and had

studied orchestration with the famous Nadia Boulanger in Paris.

Before I knew it I was hired.Photo: Rebekah Harkness, at work. composing. My work for the Metropolitan Opera Ballet over at Lincoln Center was really for an opera company, so The Harkness Ballet was really the first American ballet company to have a resident choreologist on staff. Mrs. Harkness was hardly aware of this and probably couldn’t have cared less. She hired people right and left, and fired them just as quickly. She had private dance lessons from the most famous teachers, then got tired of them and went on to something else. At that time she was deeply involved in Spanish dancing. Don Jose de Udeata was brought from Spain to teach her privately. She had a whole collection of bata de cola (a dress with a trailing gown used for Flamenco dancing) and would sit in the back of her chauffeur driven limo with her feet up, practicing her castanets. I once asked David Howard, who was the school director, why she did not try East Indian dance for a change. He answered in a jaded tone that she, as well as the staff, had already been through that phase! My first assignment was to notate Brian MacDonald’s “Time Out Of Mind”, then Todd Bolender’s “Souvenirs” and Walter Gore’s “Eaters Of Darkness”. Walter Gore, who had been one of Marie Rambert’s principal dancers during the 30s, was one of the kindest men I’d ever met. Quiet, sensitive, even to carrying to his rehearsal an injured pigeon he had found in Central Park and setting it on the piano, then taking it back to his hotel to nurse. After two months of rehearsals the new company had a repertory and was ready to go on tour with it. All of us, dancers and staff, flew to Barcelona, Spain where Mrs. Harkness had rented Spain’s leading opera house, the Liceo, for a full month just to rehearse in every day. Then followed a tour throughout Spain. Lisbon, Rome, Paris, before a few weeks rest in Switzerland where Mrs. Harkness had one of her opulent homes in Gstad. It was a good company. The philosophy was to develop a repertory where there was no corps dancers, where every dancer was strong enough for at least semi-soloist roles, and where individuality was encouraged in each dancer.

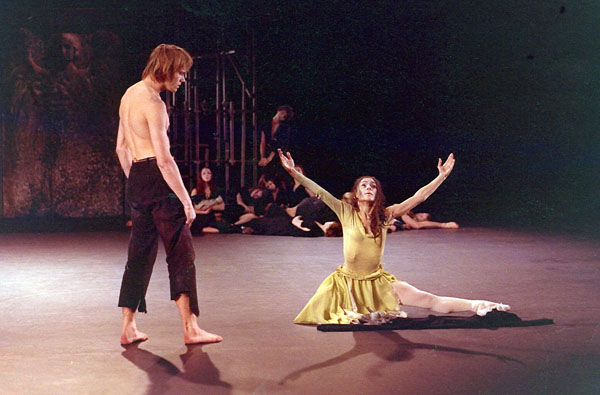

Why was it that I so often made such bad

decisions? Photo: Still from German film made of

"Eaters". Zane Wilson and Linda DiBona

Photo: Walter Gore rehearses "Eaters" He and his wife Paula, during an

evening off, invited me to join them for dinner at a Lisbon

restaurant, When we finished our meal, Walter offered what could

have been an exciting career change for me. Why not leave Harkness

to stay in Lisbon and join them and his very successful company?

They apparently were

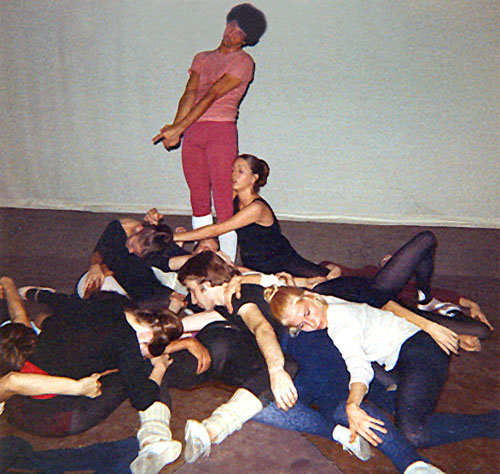

Photo: Can you imagine notating this pile-up?!

|

This

hotel was like a giant YMCA that reminded me of Sloane House (the

YMCA of my youth in New York City) except that it had a sink for

washing and a radio. This relentless radio wouldn’t change stations.

This

hotel was like a giant YMCA that reminded me of Sloane House (the

YMCA of my youth in New York City) except that it had a sink for

washing and a radio. This relentless radio wouldn’t change stations.

Photo:

The famous ‘Theater Street”. Here (on the right in the

image) is the Vaganova

Ballet Institute where Nijinsky, Nureyev, Baryshnikov, Pavlova,

Makarova and many other famous ballet stars studied and graduated.

The three in the middle of the street were fashion models as they

were doing a fashion shoot when I took the picture.

Photo:

The famous ‘Theater Street”. Here (on the right in the

image) is the Vaganova

Ballet Institute where Nijinsky, Nureyev, Baryshnikov, Pavlova,

Makarova and many other famous ballet stars studied and graduated.

The three in the middle of the street were fashion models as they

were doing a fashion shoot when I took the picture.