|

CHAPTER 12 Back At Harkness House

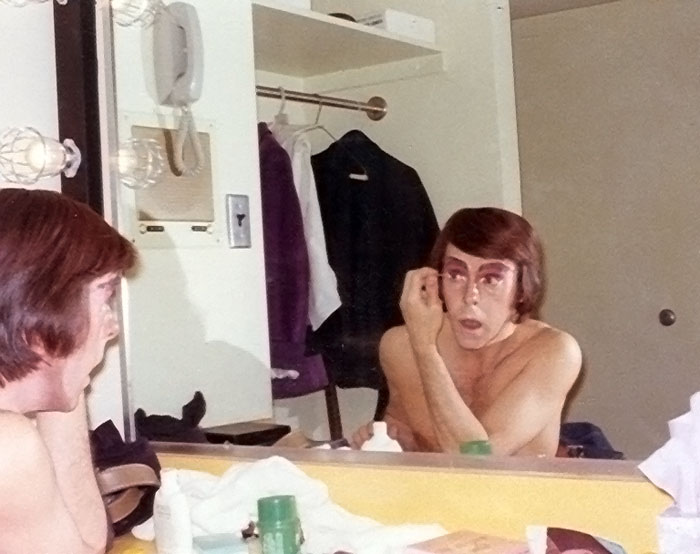

David Howard was the principal teacher of the Harkness school. He had been a member of the Royal Ballet in England and eventually became one of the most sought after teachers, not only in New York City but also as guest ballet master at schools and dance teacher conventions across the country. His rather unique method of teaching was based on circular pathways of the body, a theory I believe originated with Joanna Kneeland; a ballet teacher who Mrs. Harkness had fancied sometime before I arrived. I could be totally wrong on this but Kneeland (a kinesiologist) had made an exhaustive study of dance movement by watching films of dancers in slow motion, examining in minute detail exactly how the best dancers used their bodies. She claimed it was ‘revolutionary’ and perhaps it was. I remember David always starting his class, and probably still does, with a fast paced “therapeutic barre” rather than the traditional grand plies. Those came later. This peppy preparation certainly loosened and warmed up the body for the exercises to follow. It seemed to work and many of the famous ballet stars came to him for coaching, including Gelsey Kirkland and Natasha Makarova. I write in the past tense here as David perhaps still uses these methods and is sought after as a teacher and advisor. Sort of a guru of the ballet world. His lady co-director was a different brand and had, as far as I knew, no professional background as a dancer. A power house of energy, after a full day at Harkness House she would be off and at it again with a two hour drive at breakneck speed to her own school in Allentown, Pennsylvania for another round of classes. Naturally, her impressive connection to Harkness House attracted many invitations to be guest teacher for dance teacher conventions, yet what she taught a these prestigious outfits were usually ideas or classic dance variations learned from someone else – me for one - and passing them off as her own with not so much as a nod. She grasped at every new idea, every new book on kinesiology and taught what I called ‘the poke method’ – going around poking at parts of student’s bodies, obviously to point out the proper use of this or that muscle. Apparently it worked. A “Cinderella” that I choreographed for her student company in Allentown had some Harkness trainees thrown in - among them Patrick Swayze, a teenager yet to become the famous Hollywood movie star. She herself appeared as one of the ugly sisters, the other being another and better trained Harkness teacher, Renita Exeter, while David Howard danced the wicked Step Mother, in drag. This major cast was of course a big draw and many made the trip from Manhattan to Allentown to see it. The success of this production was followed the next year with a full-length “Sleeping Beauty”, also staged by me and featuring some Harkness trainees and guest stars Starr Danias and Burton Taylor from the Joffrey Ballet. At the final curtain, instead of inviting me to share the applause she surprisingly took all the bows as if she herself had staged it. Not that I minded in the least but afterwards the mystified dancers were asking why I hadn’t also taken a bow, as if I had for some reason refused to do so. Well, not to be unkind, I could say she probably just forgot or never bothered to learn the rules of theater etiquette. Yet her lack of tact extended into the classroom as well. When I occasionally taught a class for the trainees she would sit in front, chatting noisily to whoever was beside her – an act that would never be tolerated in her own or any other class. But to give the lady some credit, she later on did turn out a remarkable ballerina – at least one that I know of – Cynthia Harvey. The Harkness library was a beehive of activity with a steady flow of renowned personalities from the dance and theater world. Choreographers, scenic designers, conductors. I got to meet and hobnob with them all. Mrs. Harkness always gave a

elaborate parties for whatever major dance troupe came to town. The

Bolshoi Ballet, The Royal Ballet, The Moiseyev Folk Ballet. As

keeper of the keys I enjoyed taking them on tours through the house

and making them feel welcome, especially the Russians who gave me

the chance to practice their language. During his two week stay it was my job to be at all rehearsals and to notate the dance steps in detail because after he left it would be up to me to rehearse the dancers in them. Although far from being fluent, I knew Russian to the extent that I could approximately interpret his corrections and comments to the dancers. He was about 65 then and quite agile in demonstrating the steps to the dancers. During rehearsal breaks we often sat together in the first floor canteen where he answered my many questions about details in his choreography and often told me stories of how he started his own company with amateurs during the 1930s. After two weeks he returned to Moscow, leaving me to continue rehearsing his pas de deux for the upcoming tour. At a run-through, after seeing the “cocoon” dance as we called it, Mrs. Harkness decidedly did not like it and quickly dumped it but kept the “Spartacus”. It was premiered in Barcelona, Spain at the end of a month long rehearsal period at the Liceo Opera House. Mrs. Harkness had rented the huge opera house for the entire month merely to rehearse in. I left the tour in Rome to return to Harkness House and as far as I know, Mr. Moiseyev never saw our performance of his work. Long before this meeting with Igor Moiseyev, he and his work had been a major inspiration in my life. Each time his company appeared in NY I would attend every performance as well as in London and even in Moscow. It was quite a thrill for me to actually meet and work with him. I had studied his technique from several former Moiseyev dancers and when I retired to Tucson, Arizona and started my own Russian dance group, it was patterned after Moiseyev. Oddly enough, three months after he died in 2007 at the age of 101, the Moiseyev company of 78 dancers came to Tucson. I helped sponsor and arrange a master class for local dancers given by Moiseyev’s director, Elena Shcherbakova. Two of the Moiseyev dancers – a boy and a girl – readily helped the local dancers and demonstrated the steps to our astonishment. As if that was not enough, at the end of the class, Shcherbakova presented me with gifts and thanks for my life-long devotion to Russian dance and culture. It was a day I shall always

remember and treasure. Then too, there were always replacements needed for the company. These all came from the trainees and it was my job to teach them some repertory before they were accepted. There were two ballets that, oddly enough, each had a cast of six. One was all girls, one all boys. “Pas Des Fiancées” by Jack Carter

to music from Tchaikovsky’s ‘Swan Lake” had the six girls each doing

bravura variations. “Percussion For Six Men” by Vincente Nebrada was

set to drums, arranged by Lee Gurst. I had to teach both ballets in

two weeks. After seeing them perform these works, Mrs. Harkness

accepted all the trainees that I had selected. So it was yet another

new company. Her studio was locked when the first students arrived for morning class but they could hear Madam’s moans through the door. It was impossible to determine how she was struck or how many times. Missing from her purse was the $20 she brought to pay the pianist. Five hours had passed at Manhattan’s Roosevelt Hospital before she was examined. She was just left in a hallway to die. One newspaper later reported that a hospital spokesperson callously said, when asked about this neglect, “I don't know what all the fuss is about....she was just a ballet dancer”. Madame Nevelska left the Soviet Union in 1923 because her husband, an archeology professor, was considered politically suspect. She taught in Nice, France for the next 30 years. Among her students was Andre Eglevsky, who became one of the most prominent dancers in the US and a star of New York City Ballet. She had been like a mother to me, often sharing her meager lunch and allowing me to use her studio to teach notation classes, free of charge. I never paid for her classes either, which I did every morning during the late 60s and early 70s. I helped her move into Carnegie Hall when rent at her former studio became too expensive. She shared the Carnegie Hall studio with another teacher, Vladimir Konstantinov. She often invited me to dinner at her tiny apartment on 51st Street. I still have the ballet piano scores that she gave me. It’s impossible to imagine how this could happen in the renowned Carnegie Hall. Security must have been very lax. It was all over the TV evening news. The funeral service was held in her Russian church where I was driven to and from in Mrs. Harkness’ limo. Being interviewed there for TV I could only say, tearfully, how I remembered her. She weighed only 88 pounds. Fragile and bird-like. I remember [when she was mocking some student for being a bit scatter-brained] saying to me, in Russian, Nye vsyo doma, “nobody home”, while pointing to her head. She also would tell me how she found many of her students talented but lazy, without knowing that they are so. “They take five, six lessons a day! Jazz, modern, everything! But they don’t know how to work. One class should be exhausting if you really work”. I always made sure I worked in

class for her.

Photos: In class at Madam Nevelska’s small

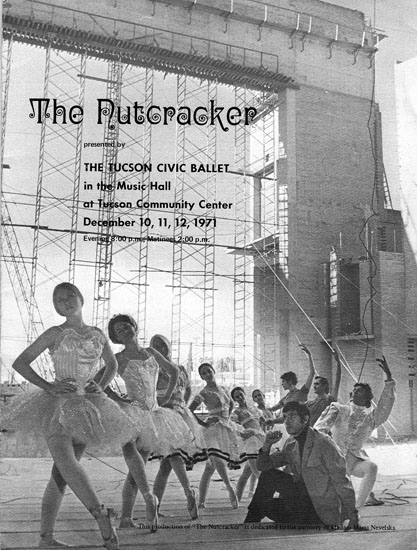

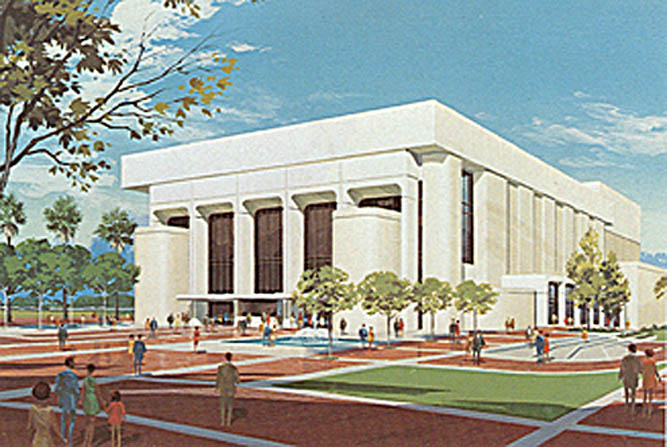

Carnegie Hall studio. Tucson was also building its new Convention Center, including a Music Hall where the Civic Ballet would perform. The Tucson Civic Ballet had the honor of being the very first event to open the newly built Music Hall, except no one in Tucson seemed to know about it.

Photo Left: Music Hall completed in 1971 |

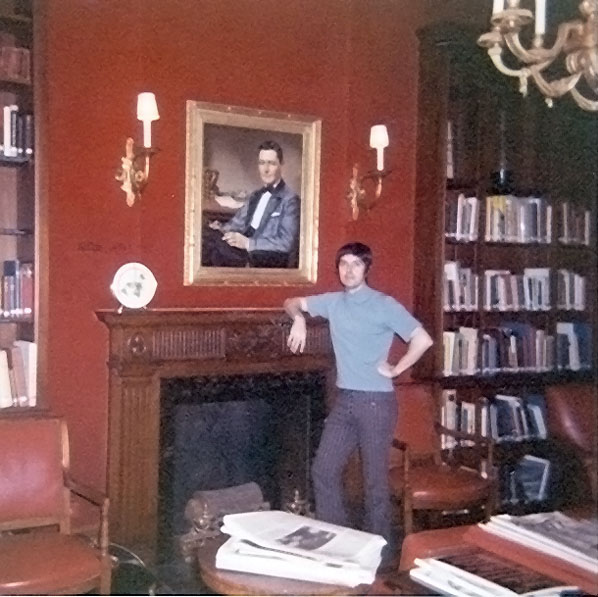

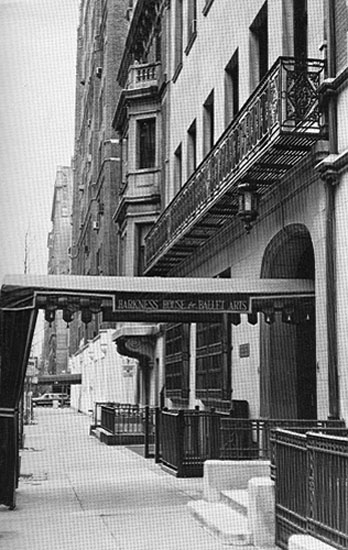

Built in 1896, Harkness House was the former home of Thomas J.

Watson, founder of International Business Machines, until it was

completely re-modeled and costing millions, to became the permanent

home of the Harkness House for Ballet Arts in 1965.

Built in 1896, Harkness House was the former home of Thomas J.

Watson, founder of International Business Machines, until it was

completely re-modeled and costing millions, to became the permanent

home of the Harkness House for Ballet Arts in 1965.