|

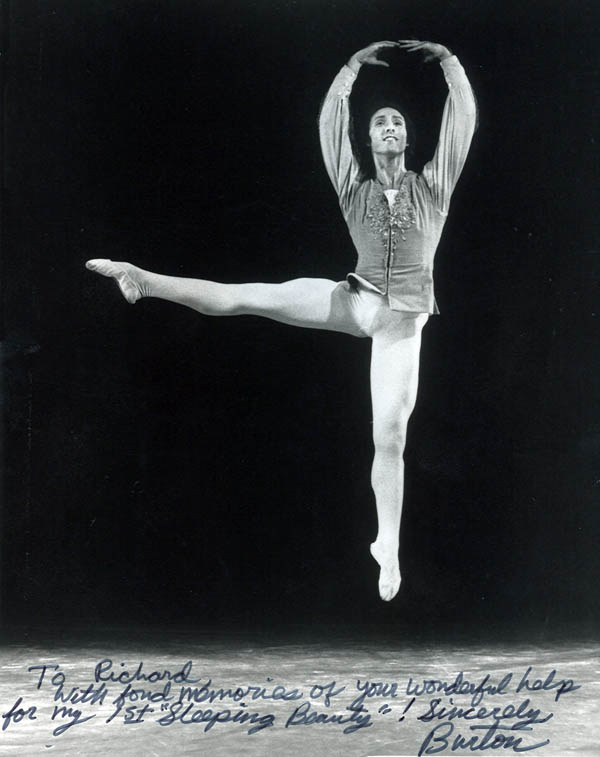

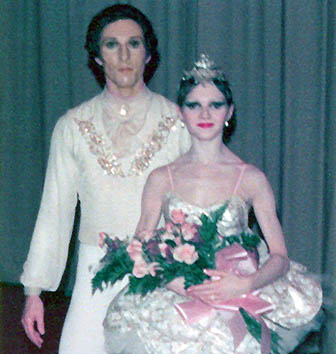

CHAPTER 17 My First Cinderella and La Bayadčre I began with a three act “Cinderella”. Michelle Lucci of the Pennsylvania Ballet danced the lead. Richard Schafer from American Ballet Theater danced the Prince with David Howard, director of Harkness House dancing the drag role of the wicked Stepmother. I couldn’t ask for a better cast. A year later, the same company invited me back to stage a full-length “Sleeping Beauty” with Starr Danias and Burton Taylor, both from the earlier “Dream” with Joffrey.

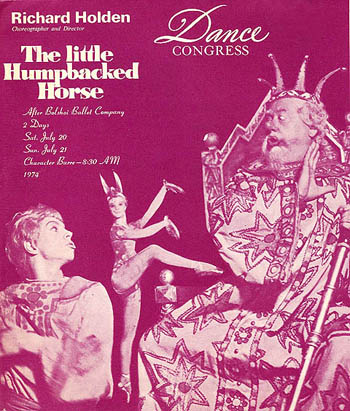

I was also staging Petipa’s “La Bayadčre” for San Francisco, Tampa, Florida, Birmingham, Alabama, Florida State University, Salt Lake City, Toronto, Canada. I was on a roll that never seemed to stop. The Humpbacked Horse I chose “Humpbacked

Horse”, a four act folk ballet based on an ancient Russian

“Skazka” (a children’s story) by Yershov. Maya Plitsetskaya and

Vladimir Vasiliev had danced it during the 60s, in a wonderful

production choreographed by Radunsky. For a month I was every day at

the

Early one morning, I found myself in the center of the huge Biltmore ballroom, surrounded by about 200 dance teachers sitting at tables. I was expecting them to come out on the floor to learn this ballet, or at least do an approximation of the steps. After all, they were supposed to take it back home to their schools in cities, towns or villages and teach it to their students. Instead they all just sat, glued at their tables, studying my 400-page book. They just sat and watched, waiting to be shown. Un-daunted, I began to dance every solo, every corps person’s part, every scene of this four-act ballet entirely by myself. I not only danced it, but at the same time also had to shout out all the counts and directions in a loud enough voice to be heard by everyone in the immense ballroom. By 10 AM I was breathless and exhausted. This couldn’t go on. For the next and final day of this madness, I frantically called some Harness trainees to come and help - to be the bodies that I needed so desperately.

Photo:

Teaching in the Biltmore ballroom, NYC I planned to teach a ballet called ‘Pas de Fiancées’, which the Harkness had done. It was a ballet with six rather difficult classical variations. The word-notes that I drew up for the teachers had full descriptions of every step and count. Before leaving, and keeping in mind the previous experience at the Biltmore, I made sure to phone the Association’s President to explain the technique required. Would the teachers be able to dance it? Yes, of course, all our teachers are professional, she assured me. I believed her and foolishly began to teach them as professionals, or at least as having a knowledge of solid classic ballet technique that they were assumed to be teaching. During my hour on the floor, to my horror, one by one they dropped out. They were not trained dancers at all but mostly overweight ladies who ran children’s dance studios. Lacking even the basic technique for these bravura variations, they just couldn’t do it and had to bow out. I again ended up dancing it all by myself, all six variations along with an entrance and coda. At least one nice lady said my notes were perfect. After lunch I had prepared to teach a Moldavian folk dance. It was an easy dance but, fearing it would be as difficult as the previous one, no one could be persuaded to come out on the floor, even though I made the concession they could do it in tap shoes. Maybe three or four took part after they were practically begged. It was a most embarrassing moment for me, but I learned a very valuable lesson. These conventions were basically for teachers to get material for their student recitals. Hadn’t I gone through the same thing when I had my own school back in Elmira? So, for the next convention in Columbus, Ohio, I arranged the simplest of dances, a goldfish dance that children could easily perform in their kiddy recitals. It was a big hit, except I felt really foolish imitating a goldfish before an astonished and amused hotel staff! The next one, run by Danny Hoctor, was in New York City at the Americana Hotel. For this they wanted Slavic character. By this time I was getting more and more well known as a character teacher. I had just written and illustrated a feature article on Character dance for a glossy magazine called, “Dance Teacher, Now” that perhaps had something to do with it. There were two sessions, one for the teachers in the morning and another in the afternoon for their gum-chewing students. I decided to make it a real presentation by dressing the part in a colorful Russian shirt and boots. Hundreds attend these conventions held in hotel ballrooms, not only in New York but also in all major American cities. The guest teachers usually stand on a platform to be seen and heard, often with an attached mike. Ballrooms, not being proper dance studios, can only supply chairs for the teachers to hold on to for barre work. A character barre is very different from a ballet barre, even though the same rules apply. A large percentage of these teachers who come to conventions, specialize in tap and jazz at their commercially based home-town schools, along with ballet and acrobatic, and sometimes baton twirling as well. Multi-tasking as they are, I always found that they can easily pick up the odd footwork of a character barre. Dynamics and expression can come later. After the center work, and to fill up the hour, I often give a brief talk about character dancing itself. This class at the Americana went along fine, but during the afternoon session - in another ballroom with the students brought along by the teachers - a minor disaster occurred. The person operating the tape recorder pushed the wrong button so there were ten uncomfortable minutes searching for the proper music. Meanwhile the students fidgeted and chatted. When we got started again, they went through the motions, in tap shoes [another concession], but it was clear to me that what most of them really wanted was more jazz and hip-hop classes, not Russian character dancing, unknown to them. This was during the 1980s. Dance teacher conventions may have changed by now but that’s what they were like back then. Ashton's Monotones It so happened that the English choreologist who had notated Monotones as well as "The Dream", was then in New York, over at the Met staging Sir Frederic’s dances for the opera, “Death In Venice”. I knew she would know the ballet first hand, having worked with Sir Frederic through the creation and rehearsals of Monotones. I would be merely teaching it second hand from her score, so I suggested to Joffrey that it might be a good idea to contact her if she would be available to teach it. There followed one of the most humiliating experiences I’ve ever had in my life! First off, when the score arrived from Covent Garden it included a note, saying I was not to be allowed to take the score off the premises. This not only prevented me from taking the score home to study before the next day’s rehearsal, but also looked to Mr. Joffrey as if I couldn’t be trusted with it, that I might make a photocopy and run off with it to illegally stage it elsewhere. Even if I had such devious plans, no responsible company would ever go along with such a scheme? This choreologist treated me not as a colleague but more or less as a servant. She certainly knew her job well and was great notator, one of the best in fact, but the dancers, seeing the way she treated me were feeling sorry. She was not well liked, not even back at the Royal Ballet as many from RB told me later on. And to think it was I who arranged for her to get the job in the first place! When she had to return to London for a week she naturally left me to rehearse the ballet. This was fine except she left by telling me that I could not proceed any further but to only rehearse what she had already taught. I was stymied. Every day I had go over and over the same steps and to fill up rehearsal time, painstakingly go over every miniscule detail in the score while the dancers wondered why they couldn’t go on. I later reported this entire unfortunate affair to the London Institute Board of Directors. As to be expected, nothing came of it. After all, what was an American doing teaching an Ashton’s work in the first place? Apparently, the Royal Ballet choreologist was above criticism. Sir John Hart’s praise of me from the stage of City Center after the premiere of Ashton’s “The Dream” meant nothing back at the Institute. Neither did all the work I’d done promoting Benesh in the USA. Fellowships went to every one of the Institute’s original, first year students except me. What was this prejudice? After Mr. Benesh’s death in 1972, a few of the British choreologists formed a council-of-management. With that seizure of power, they finally even ousted Joan Benesh, the co-inventor and founder of choreology. |