|

CHAPTER 2 Becoming an

Usher. The theater was designed after the Paris Opera and in its early days had stage shows but had turned to only showing movies, usually from Warner Brothers or Paramount. I could only imagine what it must have been like in its heyday but to me it had lost none of its splendor and seemed glamorous job for a teen-age boy. I felt I worked in a palace and indeed it was. To give an example of how movie theaters can change so drastically over the years; at that time, we teen-age ushers were first fitted into spiffy uniforms and taught to carry ourselves as if molded in a dignified, military like posture. Every afternoon, promptly at five, we marched in formation from our locker room far below up to the main floor and stood at attention while the Captain of the ushers inspected us head to toe. We had to show our shoes were polished and take off our white gloves to show our nails were clean and trimmed. We had to memorize the entire schedule in case anyone might ask when the main feature began, or ended, and were drilled on this. Only then were we assigned to our posts. Stationed at the top of each aisle we had to keep an eye on the Captain who stood at the main entrance, officiously directing patrons to whichever aisle had available seats. These Captains acted like little Napoleons. One who was particularly over-zealous was studying law and knew I wanted to be a dancer. (Many years later in New York City, I happened to be summoned for jury duty for a particular murder case. I noticed the Judge had the same name and demeanor. Even after all those years he seemed to recognize me and to be sure, he asked what kind of work I did. When I answered, in front of the entire Court, “a Choreologist with American Ballet Theater, Your Honor”, it seemed to confirm his suspicion, but nothing came of it.) Movie theaters were usually filled to capacity in those days so we had to know exactly how many seats were empty in our own aisle by periodically making a count. There was an entire language of hand signals to relay this information to the Captain. I can still remember to this day the set moves that someone must have thought up when the theater first opened in 1925 and they remained fixed all through the years until my time. It went exactly like this: Ushering

Choreography Finding the empty seats you stopped and begging the pardon of the person sitting on the aisle seat, directed the newcomers in. You thanked the standing person and then proceeded back to your station at the top of the aisle, ready to greet the next person. This routine never varied. Does this sound to you like movie

theater ushers of today? That kind of behavior is now lost in the

mists of the past but this training in posture and proper manners

were all good discipline for teen-agers and it stayed through life.

An added benefit was the constant walking up and down aisles that,

along with the bike riding, went a long way in developing my legs

for dancing. Sometimes, if stationed in a remote area of the theater

and first checking to see that no one was around, I would practice a

ballet position, a pirouette or some dance step I had just learned

that day.

The Schubert Theater Then the midnight train back to Braintree. A movie called “Escape Me Never” had Ida Lupino and Errol Flynn. Flynn played a composer who had written a ballet called “Primavera” That came near the end of the picture and the main dancers were Mlada Mladova and George Zoritch. Every time the ballet sequence came on I rushed to the front of the aisle to watch it closely, uninterrupted by patrons. George Zoritch was the first real ballet dancer I ever saw, if only in a movie.

An old story in a new setting

A Final Note on the Metropolitan Theater

Dancing With A Russian Troupe

My costume had a "rubashka" [a Russian shirt] of gold satin with red trim, lent by Russakoff and no doubt worn by him in his own dancing days. I wore this shirt for many of my modeling assignments as by then I also had a day job as an artist’s model standing motionless for twenty-minute stretches. If it was for a class of art students at the Massachusetts Institute of Art I could at least have a lunch break and talk with the other models but if I was hired out to a private studio, the session usually called for me to be embarrassingly nude. Not long after my Providence debut I repeated my tabletop dancing in Boston on the stage of the New England Conservatory Of Music where some of my fellow ushers from the Metropolitan came to watch, and finally understood what it was I was trying to do.

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo I really don’t know why I was so unimpressed by my first viewing of ballet. Perhaps I just expected too much after all the reading of the glamorous Diaghiliev days. I decided to leave ballet for a while and, for some odd reason I even thought I would join the Navy. When I boldly went for an examination I got cold feet and pretended to be color blind, a deception easily discovered! Besides, being under-age they never would have taken me anyway. Basically, I must have really loved dancing. If nothing else, it served as a means of entering some kind of different life from what I grew up with. A crutch if you will. At any rate, before long I was back at it. This time I found what I thought was a more responsible teacher, William T. Murphy, who gave a regular morning class and not the casual, indifferent lessons with Russakoff. His studio was in the basement of a building off of Copley Square, behind the gigantic Boston Public Library. Basically he was a ballroom dancer who certainly didn’t give the impression of ever having performed classical ballet. He taught from a book; the Cecchetti manual. From this book he at least was able to give some technical theory and corrections so I felt at last I was getting some training in how to dance something other than more and more prisiadkys. He of course had a low opinion of Russakoff and told me I had been wasting my time with him. Christian Science The Christian Science Center was and still is almost as big as the Vatican. The “readers”, a man and a woman, seemed to me like the parents I should have had. Always immaculately dressed and bejeweled, they were the picture of affluence and goodness. They sat on throne like chairs in the immaculate edifice. I can’t say that Christian Science healed my hearing problem. Perhaps it adjusted itself normally. Who knows, but it did eventually return to normal.

Photo: The Christian Science Mother Church in Boston I never became a

Christian Scientist but the Christian Science and New Thought

teachings seemed to help me survive through the many overwhelming

circumstances that were yet to come.

Arrival In New York City

The

Roxy Theater The last thing I wanted was to go back to being an usher but in reality there was little else I could do. Photo: The Roxy Interior

Candy Standing Still being under-age I hid that fact and told the interviewer I was a dancer (I wasn’t; I was merely a dance student). Surprisingly, on hearing this she immediately phoned backstage to ask if the house choreographer - at that time Gae Foster - had a place for me. Well, I certainly didn’t have the audacity to present myself as a dancer when I was little more than a beginner. For starters, the male Escorts - all older than I - were basically tap dancers and my training until then had only been Russakoff’s Russian folk dancing and Murphy’s basic ballet. I decided not to embarrass myself by going backstage only to be refused but at least I knew then that a dancing job was truly possible and there would be a chance for me after all somewhere in the future. I took the usher’s job.

InsideThe Roxy The famous showman, Mr. Roxy (Samuel Rothafel, who built the theater in 1927) had his own ideas back then of how his staff should be. He thought all his employees should be “with character”. His ideas had apparently taken hold and stayed until my own time there, and beyond. The Chief Quartermaster, a dwarf, had patrons staring in awe as he paraded around the Rotunda in his nifty uniform. One rather flamboyant usher would sometimes entertain the hundreds of patrons waiting on the grand staircase leading to the upper balconies by performing his acrobatic tricks. The theater was always crowded, especially on weekends and holidays. Some of Roxy’s star attractions on the stage that I remember from that time included the movie star Danny Kaye and the exotic Peruvian singer Yma Sumac (not Amy Camus from Brooklyn – name spelled backwards - as come claimed). And a surprise; Andre Eglevsky and Melissa Hayden dancing the Don Quixote pas de deux with the entire New York Philharmonic orchestra, conducted by Dimitri Metropolis. Impresario Roxy, or more likely the cultured executive of 20th Century Fox, Spyros Skouras, trying to bring to the Roxy stage real high-class entertainment as well as the standard vaudeville type acts. Then there were the movies. The now classic “All About Eve” had its New York premiere there with great excitement. The theater was closed all day to be cleaned spotless for the many celebrities that came that evening while searchlights beamed at the skies over Manhattan. Did I get a chance to see Bette Davis? None of the movie stars came near the candy stand but were quickly whisked up to the loges. There was a second candy stand in the first balcony foyer that I sometimes manned. Beside it was a small window that looked down to the Rotunda below. (This window can be seen in a 1961 Life Magazine picture of Gloria Swanson (who opened the theater in 1927) standing in the midst of rubble as the theater was being torn down). My one regret is that at the time, as a naïve kid, I didn’t fully appreciate all of the theater’s wonders. I knew the Rotunda well from looking at it every evening but as a student during the day and then six hours serving demanding and often rude patrons, all I wanted to do was to go home and rest for a morning dance class. But I sometimes did explore the rabbit warren of passageways and nooks and crannies surrounding the cavernous auditorium. Like pulpits, it was amazing to stand inside them and look down at the nearly 4,000 people sitting below. Wandering backstage I saw the giant stage from the wings, the rehearsal studios and the various production departments. I discovered this vast area was, oddly enough, built into a corner. Apparently, in order to make it fit into the lot, the entire theater was built at a 45-degree angle from 50th towards 51st Street., (“The Last Remaining Seats” by Ben Hall has the history and many pictures of this marvelous, long gone “Cathedral Of The Motion Pictures”). Now, so many years later, we can only wonder why such a wondrous place could disappear so quickly. Since that time I have danced in theaters all over the world but the Roxy somehow stays fixed in my memory. It kept me alive during those difficult years and served as my first humble step into the New York world of show business. George Chaffee My first proper ballet teacher

in New York was George Chaffee. In exchange for

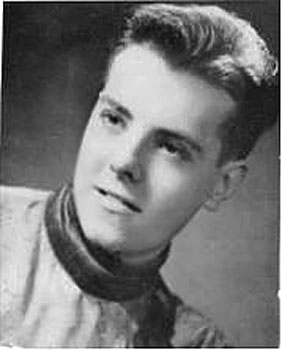

Photo left: George Chaffee - Photo below: Me as Harlequin When the company made a tour to

Atlanta. Georgia, the Roxy gave me the week off to go. We stayed at

a hotel across the street from the Fox Theater, famous for being

where “Gone With The Much of Chaffee’s work was re-creating ballets in the French style of the 18th century. For this tour I danced , with Eve Beck, a minuet from the ballet "Les Caractères de la Danse”. Decked in the authentic and overly elaborate costumes with feathered headpieces as in the Court of Louis XIV we were barely distinguishable from each other. In New York’s Cooper Union and the Henry Street Playhouse, something called “Piccolini” had me doing a Harlequin dance.

Broadway There was one Broadway musical audition where I was picked out of about a hundred other dancers. “Plain And Fancy” was about the Amish people and it turned out they were actually looking for a short dancer as a replacement. Helen Tamiris was the choreographer. During one of the dance combinations, her male assistant said to me in a hushed voice, “you’d better smile if you want the job”. Was this a hint? From then on I beamed with every step. There’s a song in “A Chorus Line”: (Oh God, I need this job). That was exactly how I felt at that audition. Then, the dancer I was to replace decided not to leave after all so it was back to the Roxy.

The Metropolitan Opera Ballet School There was really no other ballet school in New York, or the entire country for that matter, that was quite like it. Because of its proximity to the stage it had the atmosphere of the theater about it and you could easily feel you were a part of it all. This old, musty and cluttered building stood on Broadway between 39th and 40th Streets. The stage door on 40th Street side led to an ancient elevator which took you to an upper floor and from there you had to climb a staircase further on up to the roof stage to the ballet studio. My class was every morning at ten o’clock, then a walk through Times Square to the Roxy and my regular job. I felt I was in heaven being within the hallowed walls of the Met that I had so often listened to on the radio back home in Braintree. One Saturday afternoon I became a walk-on and carried a spear in “Aida”. Marina Svetlova and Leon Varkas were the principal dancers and I made sure I got into a good position on stage to watch them perform. I made friends with other students, mostly Cuban boys my own age and a girl, Aurele Pelton who lived in Valley Stream, Long Island. When she got a job with the Radio City Music Hall ballet company she asked if I would take over classes at her school. Teaching was entirely new to me but I welcomed the chance to make some extra money, even if it meant traveling to Far Rockaway on the train every Saturday morning. It was a school filled with children; horribly spoiled children who were constantly playing pranks. You had to keep aware what was going on behind your back and being inexperienced I often didn’t know exactly how to deal with them or what to teach. Aurele’s mother who played the piano for the classes, often had to step in and tell me what to do. But the extra money, added to my meager Roxy salary made me feel suddenly rich. One evening on the train back to Manhattan I happened to read the headlines on a newspaper someone was holding. It was April 8th 1950 and the headline was NIJINSKY DEAD! He had died in England after a long illness at the age of 60. No film exists of his dancing. The photographs give only a faint hint of his genius. He danced in public for only ten years before insanity took over his life, yet the legend refuses to die. Many top male dancers of today have the technical skill to easily out-dance him, but during his brief career he was without peer. The Tudor/Craske

Regime Tudor had the highest reputation and had already created most of his famous ballets. His classes were nerve wracking because you were never sure when he was going to embarrass you with some acid remark. When my month’s tuition ran out I asked Miss Harding for a scholarship but she now had to ask Tudor. I sensed she was disappointed when he took one look at me and refused. (I speak a lot more about Tudor in another chapter). Realizing I was needy and feeling sorry for me she offered me what she could; a chance to be a regular supernumerary in the operas. They paid $2.00 a performance. In “Rigoletto” I was one of four court musicians placed on a balcony when the curtain opened. We mimed playing the instruments while the dancers performed below. This was a brand new production and even we supers were sent to the great Karinska for costume fittings. With her mascara smearing down her face, Karinska placed a white, pumpkin shaped hat on me and exclaimed how ‘handsome’ I looked with my innocent, boyish face, sad green eyes and bangs jutting out from under the hat. Donald Mahler was another class-mate and supernumerary playing a faux instrument beside me in those bright, new costumes. It was a spanking new production designed by Eugene Berman. We would look down from our on-stage balcony perch at the dancers below and dream that one day we also could be doing the same. Donald remained with the Met ballet school, later becoming a Met dancer and was still there when I joined the Met as resident choreologist in 1966. He eventually became the Met's ballet master, replacing Dame Alicia Markova after the long nine-month strike of 1969 when so many left, including myself. Afterwards he became an authority on several of Antony Tudor's works that he stages for major companies worldwide. (In 1966 when we were both dancing in the newly built Met in Lincoln Center they were still doing that same production of Rigoletto. By then we were regular company artists of the ballet and a new set of supers were up on the balcony, playing the same instruments and wearing the same costumes we once wore. The beautiful hats that Karinska had made and fitted had by then become tattered and threadbare. Would our names still be inside I wondered.) The Met was also doing a new production of “Aida” to open the season. Margharita Wallman, a ferocious and demanding woman, was stage director who decided to make a complete break with past tradition and be very particular about what the supers should look like. She actually auditioned them, whereas before they would either be ballet students from the school or else practically anyone who happened to walk in off the street. She wanted them all to be tall and muscular; the hefty football types. That of course left me out. But after opening night and the college guys she hired had experienced the fun of appearing in an opera, it was back to using what was available. So, for the rest of the year and into the next, I continued as a walk-on in AIDA and in all the other operas that went on that season.Bronislava Nijinska And The Ballet Theater School When Lucia Chase opened the Ballet Theater School on West 56th Street it was the official school for the company and she was very excited about it. Bronislava Nijinska herself was head of the faculty. Other teachers were Anatole  Vilzak,

Ludmilla Schollar, William Dollar, Edward Caton and later, Valentina

Peryaslavec. I decided to give it a try and did Nijinska’s class.

This was the great Bronislava Nijinska, sister of Vaslav whose life

story had inspired me to dance in the first place. Here I was,

actually in her presence and taking instruction from her. She did

not speak any English and was very frightening in her black silk

pajama suit and clenching a long cigarette holder. This was the same

image she left with thousands of other dancers. Her husband sat in

the corner of the studio, translating her corrections to us.

Afterwards, I somehow mustered up the nerve to ask her, in Russian,

if I could by any chance have a scholarship as I did not have any

money to pay for lessons. Vilzak,

Ludmilla Schollar, William Dollar, Edward Caton and later, Valentina

Peryaslavec. I decided to give it a try and did Nijinska’s class.

This was the great Bronislava Nijinska, sister of Vaslav whose life

story had inspired me to dance in the first place. Here I was,

actually in her presence and taking instruction from her. She did

not speak any English and was very frightening in her black silk

pajama suit and clenching a long cigarette holder. This was the same

image she left with thousands of other dancers. Her husband sat in

the corner of the studio, translating her corrections to us.

Afterwards, I somehow mustered up the nerve to ask her, in Russian,

if I could by any chance have a scholarship as I did not have any

money to pay for lessons.

Photo: Bronislava Nijinska Her answer was "Da, Konyeshno” (yes, certainly). Whether this was because she had seen some great potential in me or because I happened to be the only boy in the class I have no way of knowing. I rather think it was a bit of both because she thereafter seemed to show a great deal of attention and interest in me. Unfortunately, it was not too long before she was gone. The reasons were not clear. Studio politics of some kind I was told concerning her and William Dollar. At any rate, I stayed on in spite of continually being summoned upstairs to the company office to be asked to pay at least some tuition, even if only half. Unlike today, scholarships for boys were not so freely given. Elena Balieff, another imposing white Russian lady, was the school director. Perhaps she had put in a word for me. Vilzak and Schollar were the main teachers. Both were from the Maryinsky in St. Petersburg. Ludmilla had actually danced with Nijinsky. It is incredible to think that 45 years later Vilzak was still teaching and he was rather old back then in my time. Edward Caton’s classes were a bit tiresome for me but he had a personality that was amusing. With his grating, scratchy voice due to a previous throat operation, he would bark to the pianist, Valya Vishnevskaya: “Valya, Valse, pozhalusta”. [Valya, a waltz please]. Then Valya, another Soviet refugee, would take off with a lilting, dancy waltz.

My steady girl friend at that time, Joan Josephson, was working in a nearby Woolworth’s. Stopping by one afternoon to pick up Joan, my favorite teacher, Mme. Schollar happened to come along. After introducing them I mentioned that Madam had actually once danced with Nijinsky. To my amazement, Madam then actually said that in class I danced even better than he did! I couldn’t believe my ears. That could not be possible. Photo left: Joan Josephson Could it be Nijinsky wasn’t as great as we are led to believe? Apart from his remarkable dramatic abilities, clearly seen from his photographs, (there are no films of his actual dancing) it’s doubtful if he could match the pure technical prowess of today’s star dancers. Then of course, Mme. Schollar possibly just didn’t like him back then, or even get on with him. I figured that the only possible reason she could have said this was that she thought my girl friend would be impressed on hearing it.

Photo: Yurek Lazovsky Then there was Yurek Lazovsky’s twice weekly character* classes. At that time, Lazovsky was the only well-known teacher of ‘character’ in New York. He was on the faculty of nearly every major ballet school in and around the city and shuttled from studio to studio in a never-ending grind of classes. A patient and kindly man, I can still see him, carefully demonstrating for every newcomer, and there was always a newcomer in the class, each exercise of his ‘set’ barre. From my previous experience with Russakoff I had no trouble picking up his steps and technique and he seemed to take a fatherly interest in me. I wore the red boots that I had actually stolen from the Met’s “Khovanschina” and I felt quite the Russian Cossack. Before long, Lazovsky took me into his short-lived Polish/American dance company. We were touring the Polish opera, “Halka” and performing its mazurka and polonaise in bright new costumes. In each city, after the performance, there would be a late supper with Lazovsky’s friends from the Polish community. As hungry dancers we naturally looked forward to these, but also to the singing and dancing that usually followed. Later, as a soloist with the Metropolitan Opera, where character dancing is so often highlighted, I found this early link with Lazovsky very valuable. Supering At The Met The performances with Flagstad were unforgettable. She was a large woman, with beautiful, translucent skin and bright, shining eyes. In one scene we were all posed as Greek statues at the top of a staircase which she had to ascend. Climbing towards us and gasping for breath she would say to us with her back to the audience how she wished she were a dancer like us. Imagine how elated we students were on hearing this. At the final performance, Flagstad was taking endless curtain calls and the General Manager Rudolph Bing brought her a glass of champagne that she drank right on stage, then threw the glass into the wings, breaking it into pieces. This gesture thrilled the audience that continued to applaud well into the night. Another opera was Massenet’s “Manon”. Victoria de los Angeles made her entrance in a horse pulled coach while I, as a stable boy, meandered about the giant stage set. At some point, baskets of real bread and apples were given out. I don’t know the reason why these were there but since I had no money for food all day and probably wouldn’t, I made sure to get some and went into part of the set, an on stage gazebo and ate. That’s about how poor I was. There was another super, Bill Aubrey, a dance student who lived hand to mouth as I did. To my amazement, he once told me he would read nothing but poetry: a statement I found hard to believe. We supers were kept in a kind of dungeon under the stage, always freezing cold in winter. Even so, we were so entirely devoted to what we were doing that we arrived way before time to go on. Probably it would be just holding a candelabra during one act of ‘Marriage Of Figaro” or running on stage in the final moments of ‘Die Gotterdammerung’. Regardless, we would spend hours making up for just that one appearance. Many of the regular supers were opera lovers as well and did it just to be on stage to hear their favorite singers. In between, I managed to land a job at Radio City Music Hall doing four shows a day along with a first run feature movie. On that immense stage I found myself having to make my entrance from, of all places, a dizzying height high above. While waiting for my cue I had to stand on a tiny platform looking at 36 dancers far below until, suspended by a thin wire I was lowered to the stage floor. It was an underwater scene where I danced a few solo steps then lifted and carried off the leading ballerina. The run lasted about 4 weeks, then another 4 weeks with a full ballet of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody In Blue”. The Radio City Rockettes joined the corps de ballet on this one making a stage full of about 60 dancers with 5 boys added (me one of them) dancing upstage a few steps on a tilted, mirrored floor. Another scene had me dressed as a cowboy twirling a lasso while being lifted by hydraulics from the orchestra pit. The Common Glory

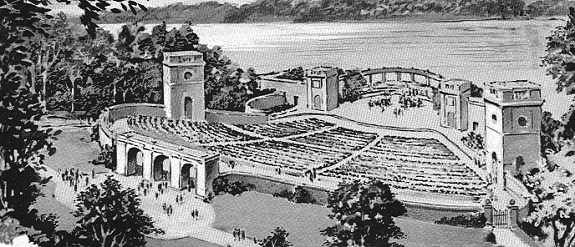

There were eight of us boy dancers and an equal number of girls. We shared apartments and rehearsed in the gym of the College of William & Mary, then on the vast stage of the outdoor amphitheater where the production went on. One of the steps I had to perform, as a Colonial American settler, was crossing the stage in a series of jumps landing in a wide 2nd position. Since it was a cement stage, at the end of the day my thighs were so sore I could barely walk. I begged to be let out of this step but Myra said that she particularly liked my “‘bouncy” quality and I would have to stay in it. Behind the stage was a lake on which they had placed mock battleships as part of the play. It was the time of the Revolutionary war. We had to do a harvester’s dance, a pioneer dance, and a minuet and finish off with a maypole dance. Every evening, directly after the performance we had to unravel the maypole ribbons. We also had to fight in the big battle scenes, either as American soldiers or British red coats. Every evening we would have fun deciding which side we would take. It didn’t matter. We changed back and forth to avoid monotony. There were actors playing Washington or Jefferson, some who later became famous. Goldie Hawn also danced in The Common Glory at the beginning of her career. On the 4th of July we were marshaled into appearing in the town in costume as part of the re-enactment of the reading of the Declaration Of Independence from the balcony of the Governor’s Palace. This was in fact the actual place in history where it was read. Each of us were assigned to posts along the main street and were supposed to join in the procession to the mansion and there listen to the Declaration. Afterwards we were to perform our maypole dance from the production for the tourists, who were everywhere to witness this historical spectacle. The summer wore on. Each evening we hoped for rain as that meant the performance would be cancelled and we could have the night off. There were trips to Yorktown battlefield and drinking ale at the famous Chowning’s local tavern.

Towards summer’s end we gave a dance concert. I choreographed a pas de deux to Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony. I called it simply “Prokofiev”. The leading ‘ballerina” from the pageant and I danced it. It was my first effort at choreography. Photo: Rehearsing on the stage in Willamsburg The summer over, we all headed in our own directions, I back to New York and Sloane House YMCA. Resuming my classes at Ballet Theater school, Madam Balieff said I had lost weight and looked terrible. I thought I looked sleek and trim. * Character Dance is folk dance done from a base of ballet technique.

|

Photo:

In Senia Russakoff's Rubashka

Photo:

In Senia Russakoff's Rubashka