|

CHAPTER 3 St. Petersburg – Florida, not

Russia. Jamie Jamison, one of Agnes de Mille’s star dancers and leading dancer in the Broadway musical, “Brigadoon” was holding a dance audition for St. Petersburg, Florida. He was going to choreograph eight musicals for a winter stock season there. Jamie was an expert in Scottish dance (reason for Scottish solo in “Brigadoon”) and I remembered him from some classes at Tatiana Chamie’s studio (200 West 57th St.) where I had gone occasionally during my first year in New York. (Tuition was $1 a class, handed to Tanya on your way out). Jamie would not have noticed me as I was just an inept beginner in the morning class at that time, but what I noticed about him was the cleanliness and tidyness of his dance bag, due perhaps to training at some military school he had gone to as a boy. My girl friend, at that time, and I, decided to go to the open call in Steinway Hall on 57th Street, but not expecting anything to come of it. I had already auditioned for several Broadway shows and had always been called back for a second look; sort of like being put on the short list. Being ‘called back’ was a hint that you were acceptable and they were interested, but these finals always ended with rejection, not because of my dance ability but because of my short height or that I couldn’t sing. I was convinced I was just not the Broadway type they were looking for and never would be. When Jamie Jamison and the

producers were ready to make the final selection, I was called

forward to stand in a line and found myself between two other boys,

both taller. This is where they will say “thank you” and let me go,

I thought. Before they could say that, I decided to use a little

trick that I’d used before, though it never really worked. I found I

could grow at least a half

Photo: Jamie Jamison I was sent immediately to the Actors' Equity office to join, then to Eave’s costume house for fittings. I wondered, could it be that my act of introducing myself to Jamison and shaking his hand at the beginning had made an impression? Ordinarily I would have stayed in the background, hoping I would be noticed. Had I finally learned that my innate shyness and reticence had no place in the dance world? Or, was I just trying to impress my girlfriend as being more aggressive. Feeling elated, I went straight away to the drug store on Times Square that always had a makeup kit displayed in its window. I had so often stood and gazed at that kit of theatrical greasepaint, longing to own it and be in a position to put it to use. Now it could be mine. I had been to St. Petersburg once before for a short time (about a month) working long hours dishing food in a cafeteria and as a bus boy at a beach hotel. A kind lady rented me her garden tool shed, just big enough for a cot to sleep on. Now it would be a different story. Flying down to Florida was my first time in an airplane. As soon as we arrived, rehearsals began for our opening musical, “Carousel”. “Kiss Me Kate”. “Annie Get Your Gun” and others followed. There was a steady stream of principals arriving from New York to take the leads. Charles Nelson Riley, later to become famous on Broadway and TV as a comic, was a member of our chorus. It was not a proper theater but ‘in the round’, meaning you had to make entrances and exits up and down the aisles. In the beach ballet of “Carousel” we had to dance in bare feet. Ready for our entrance down the aisles, one of us spotted a scorpion in the middle of the stage. What to do? Fortunately, someone in the front row saw it and removed it just as we ran to the stage.

On returning to New York I found a small room in Greenwich Village and went back to classes at Chaffee’s studio. The small savings from St. Petersburg soon dwindled but during one evening class an observer singled me out for a job at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn to pose for art students. Soon I was posing for private sessions with artists around Manhattan and was able to make a small living. I’ve often thought there must be, to this day, thousands of portraits of me floating around. Oddly, during my ten-minute breaks from posing I never once glanced at any of these paintings to see what they looked like. Probably because I didn’t want to appear interested. Being an artist’s model is a tedious job at best. For a dancer, holding difficult dance poses all day long can be exhausting. A dancer’s nature, as any dancer will tell you, is to move, not to be immobile. There was, however, a brief job that had some action. My running and leaping on a platform at an animation studio was drawn into Mighty Mouse leaping up to a mountain top. My filmed pirouettes eventually turned into a blurring spin by the cartoon mouse. These modeling jobs and even for a while confined in some sort of costume contraption as Mr. Peanut in Times Square, kept me going. As Mr. Peanut my arms and legs were the only part of me showing as I peered out through a hole in the head to hand out peanuts to passers by.

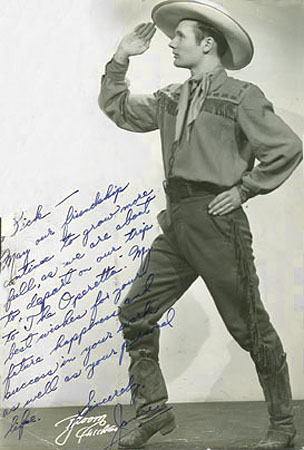

Dancing jobs were scarce at that time of year as most auditions had already passed. Walking past a Times Square newsstand I happened to see a curious announcement in “Show Business” (a Broadway casting paper). It was for dancers to go to Kennebunkport, Maine for a summer season of light opera. It was an unpaid job but with free room and board. As an Equity member I should have rejected anything on the spot that didn’t pay, but the thought of a sweltering and jobless summer in New York City was hardly inviting so I went to the audition, held in Katherine Dunham’s studio on West 43rd Street. The choreographer was a fellow named Roland Wingfield. Since very few dancers were willing to take a non-salaried job, I turned out to be the only one auditioning. In fact, Wingfield seemed relieved that anyone showed up at all and accepted me on the spot. When I arrived in Kennebunkport, I found only one other male dancer. Surprisingly, he happened to be David Beagleman, a classmate at Chaffee’s studio. David was just as surprised to see me. He had changed his name to David Villon, after the French poet and thief, François Villon. Clever, I thought, he was already making career moves. Not so, as David didn’t stay a dancer very long. Several years later I ran into him in New York. He had married a flamenco dancer and become a psychiatrist.

Photo:

Posed in front of “Windfall”.

The small opera company, called Arundel Opera Theater, was run by a tenor, Wesley Boynton, and his partner, Morse Haithwaite. Both were probably in their early fifties. Morse acted as conductor, pianist, vocal coach, stage director and general administrator. Wesley, as far as I could tell, concentrated mainly on his own singing. They lived in a large house called Endcliffe, where I assumed Wesley had grown up. His mother was still there. The female singers and dancers also shared this house while the rest of us were scattered in two other buildings on the compound. One was called “The Studio” which had a miniature rehearsal space and upstairs sleeping quarters. Over a hill was another structure called “Windfall” which housed the technical shops and had living space for fourteen. There were perhaps a dozen or so singers to perform the summer offerings: “Merry Widow”, “Pagliacci” “Chocolate Soldier”, Marriage Of Figaro”, “Vagabond King”, “Carmen”, “Gypsy Baron”, the typical summer stock fare but an ambitious repertory for such a small outfit. With one or two exceptions (because some of them may have been paid) I suspected they were there either for theatrical experience or to enjoy a free summer getaway. We performed a different opera every weekend on the Kennebunk Town Hall stage, a half hour drive away. We were transported back and forth in a dilapidated 1926 vintage bus, always driven by Morse. It was like a family. That summer they had begun plans to build their own theater. Consequently, after every meal in the main house where we all ate together, Morse would tinkle his glass for attention and then gleefully announce how much closer they were to getting the necessary funds to build it. There were sizable audiences for every performance so there seemed to be a pressing need for a larger theater. I, on the other hand was completely penniless. I could never join the others as they went every evening down to the seaside village to indulge in lobster sandwiches - a Maine delicacy. I always begged off, claiming I wasn’t hungry, but Morse saw through my charade. I suppose, feeling sorry for me, he asked me to create hats for the Mikado production, which earned me a few dollars. Then I sent off an article, hand written, to The Christian Science Monitor in Boston. Surprisingly they published it straightaway and paid me. This in fact was my very first piece of published writing and it was done out of desperation, yet it turned out to be the modest beginnings of my writing career. All the leading male roles were taken by Wesley himself with accompaniment provided by Morse at the piano. During one performance of “The Mikado”, Wesley missed his cue and was nowhere to be found. We were all searching frantically for him while Morse covered as best he could, saying Wesley’s lines from his seat at the piano in the pit and providing extra music. Finally Wesley bounded on stage. There very likely was a big quarrel between them that night! Jackson Wiley was the choral director. Oddly enough, well I suppose not all that odd as the theatrical world is a small one, years later he happened to turn up again as the orchestra conductor at Butler University in Indianapolis while I was a professor there. At some point during the summer we were invited to perform "The Merry Widow” on board a battleship anchored a mile off Cape Arundel. It was ridiculous trying to dance on a deck rocked by giant ocean waves, and amazingly, none of us fell overboard while the crew of sailors laughed at us teetering on the edge of the ship. Another unusual event was on Independence Day when the entire opera company was asked to march in the town parade. We dancers decided not to merely march along like everybody else but to dance along instead. It was a foolish decision. While sprightly dancing along the paved streets of Kennebunk, I looked down and suddenly realized I was wearing my one and only pair of already worn out shoes! As I lacked a warm winter coat, or any coat for that matter, I wondered how I was going to survive during the coming winter in New York City, now shoeless as well. I was later to find out, and make use of, Actor’s Equity, who supplied a coupon for a pair of shoes for needy members. In August, close to my birthday, it was suggested we all take a day off trip to Portland and then a boat out to one of the islands off coast. Each of us had to contribute ten dollars for this adventure. Rather than admit to being destitute of any cash I pretended that I preferred to stay behind. Raymond Keast, the company’s leading baritone from New York City Opera, saw through my subterfuge. I suppose, feeling sorry for a penniless young dancer, he kindly and secretly supplied my fee. The choreographer, Wingfield, thought of himself as something of a modern dance pioneer and was constantly filling notebooks with exercises in what he called “The Wingfield Technique”. Coming as I did from the highly professional classes of Nijinska, Vilzak, Schollar and Valentina Pereyaslavic who taught the Vaganova technique, I thought his exercises seemed grotesque and silly and I absolutely hated doing them. In fact, I hated them so much that one morning during company class I refused to do them any longer and took the nearest chair, angrily hurled it across the studio floor and walked out. This was of course a foolish and childish thing to do and it naturally infuriated Wingfield who promptly complained of my behavior to Morse. Conversely, Morse was delighted by the theatrics of it all, particularly as the incident happened in front of some wealthy local ladies who took morning class with us. He felt this show of artistic temperament added a touch of theatrical glamour to our troupe. Apart from being impoverished, I really enjoyed that summer. Swimming in the icy waters of Kennebunkport beach and the clean ocean air combined with the wholesome food made me look and feel healthy and robust. The summer ended and I bravely headed back to New York, determined as ever to find a place for myself on the stage. Exactly 40 years later, during the summer of 1993, while visiting my sister in Scituate, Massachusetts, I drove up to Kennebunkport on a nostalgia trip, to see if I could find any of these places of long ago. I, who always had an accurate memory and sense of direction, spent an entire afternoon trying to find the compound, but with no luck, as if it had disappeared. It was like the musical “Brigadoon” where two Americans on a trip to Scotland become lost and encounter a small village called Brigadoon, not on any map, in which people behave as if they were living two hundred years in the past. I talked to some old folks. One or two remembered the Arundel Opera and Morse and Wesley. It was not until a year later that I received unexpectedly in the mail a package of programs and pictures, kindly sent by the town museum keeper. It included an obituary of Wesley’s death at the age of 90! He had lived a long life. Back in New York (1953) I got a job with a publishing firm, Abelard Press. All I had to do was write out the rejections slips for the (already read manuscripts) for return to the writers. Then, after a few of months, Abelard merged with Shulman. As usual with any merger it caused a clean sweep and I was again out of work, and just as I had finished paying off the employment agency that got me the job! |

Photo:

Photo: