|

CHAPTER 8 Everyone Will Be Famous For 15 Minutes - Andy

Warhol In any case, I was able to enjoy a brief period of celebrity with interviews for Time magazine, New York magazine, Newspapers, Radio and TV talk shows. I was asked to write articles about my work for glossy magazines such as “New York Magazine”. “Dance Magazine”, “Opera News”. In a sense, it was hard to believe, and beyond the bounds of probability that this attention was really happening to a choreologist - a job that was considered by some to be little more than that of a glorified secretary. Part of my job was to attend rehearsals and performances and eventually notate every bit of dancing that passed before my eyes. I suppose that many asked why did Dame Alicia want to keep this written record of opera ballets? Well, for starters, it had everyday uses as a tool in the Met’s everyday operations. The choreographer or ballet mistress could, and often did, forget a step or dance sequence that was set earlier. I could demonstrate the missing steps from my notes and the rehearsal could go on, whereas before, dancers just fumbled around trying to remember. In a sense, the notation is like the minutes of a meeting: more exact, more reliable than anyone’s memory and with this document the rehearsal can go on to new business. When the choreography for a ballet is finished – granting the contradiction in terms here since choreography is never ‘finished’ in the static sense – I prepared a final score from my rough rehearsal notes. This final version made it possible for a far more economical use of the, always limited, rehearsal time. It could be used for teaching roles to cast replacements, or for that matter to whole new casts in future revivals. As for long-range benefits, the final version may be salable to another company, or it can be lent to or even exchanged with a cooperating company. Because of the efficiency of production based on choreographic scores, choreologists are often asked to stage a work for another company. The choreography of a ballet thus preserved can be transmitted across oceans and down generations, just as the plans for a building enable a builder to reconstruct it, even centuries later. Choreology offers a universal written language. It preserves a dance, but also a dance that can be stolen. Therefore, choreology offers the protection of international copyright.

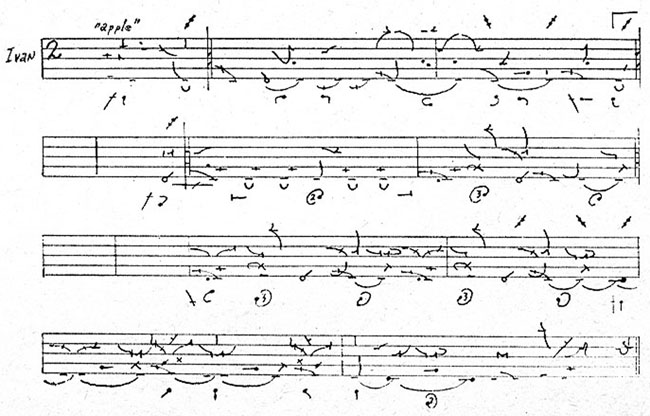

My Method Of Creating A Benesh Notation Score

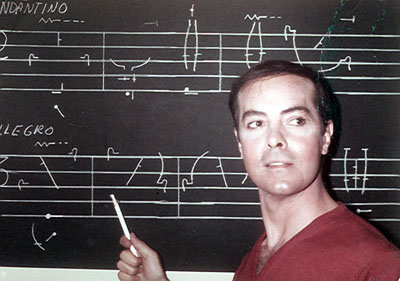

Photo: Teaching a class in Benesh Notation Producing a Benesh score often involves eliminating nonessentials and searching out clearer ways of stating a movement. This is to avoid redundancy. When dress rehearsals begin there is always more work in checking over the rough working score against the performance and the exact placement of the dancers within the stage set. From all this material I prepare a master score, looking something like an orchestral score. Naturally, the more work put into a score, the fuller and richer it becomes. Even after it is complete, I continue to attend rehearsals and performances to check for any detail that might have been missed, or to see if the choreographer has made a change that would put the score out of date. Benesh Notation Sample: Paris' variation with the Golden Apple from Dame Alicia's choreography for "Adrianna Lecouvreur"

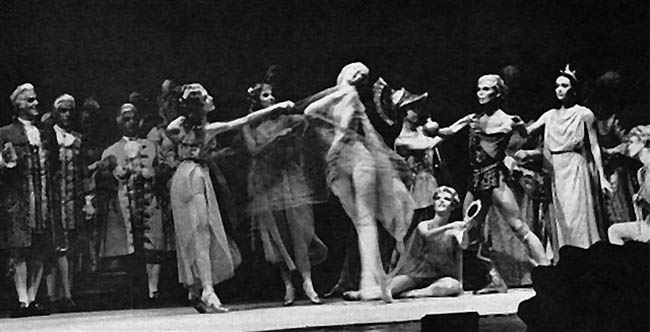

Photo Below: The actual scene as described by the

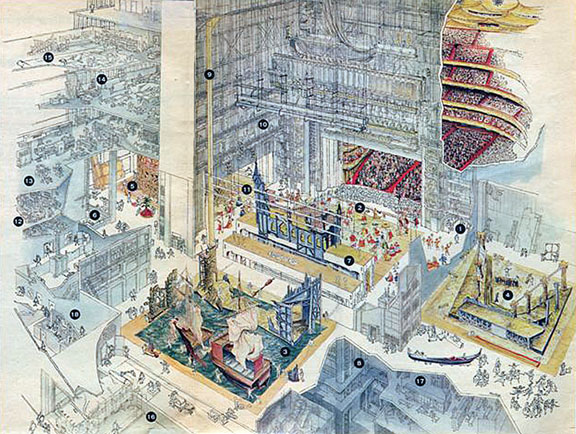

notation sample Backstage At The Met Then there is the immense amount of opera-scenery, pillars, staircases, even full houses that have to be considered. Classic ballets also have these but at the new Met it had reached monumental proportions. Inside The Metropolitan

Opera House

Photo: Cutaway drawing of Met interior viewed

from backstage A quick glance at a video is helpful in learning a dance. I always found it an invaluable tool for myself but it does not have the details notation does, just as a music CD doesn’t obviate the need for printed music. I’m often amazed at how young dancers of today seem able to easily pick up a dance just by watching a video of it. It’s a skill I never acquired, but on close analysis it turns out they end up with just an imitation of what someone else is doing. For the most part, videos give an unfair picture of the dance. The lighting may be poor, details of the movement may be hidden by other dancers, props, or costumes. Entrances and exits can be missing or the dancer you are watching may be giving a really bad performance. Learning a dance from video is a wonderful aid, but also consider that you may be studying a poor copy of what the choreographer never intended in the first place. Further on I will write about how dance notation in the USA has frankly become a dying art. This is not so in Europe where dance companies use sometimes three or four choreologists on staff. My final job as a resident choreologist was with American Ballet Theater. I was their first and only. After I left there were two or three others that came and went. Then the company began to rely totally on video for revivals, unless one of the European companies sent a choreologist to set a work by a major choreographer such as Ashton, MacMillan, Cranko, etc. In America, the government is not nearly as generous with the arts as in Europe or elsewhere. There just isn’t the money to have the luxury of a resident choreologist on staff. |

All

this is due to the genius of Rudolph and Joan Benesh.

All

this is due to the genius of Rudolph and Joan Benesh. After

this rough copy is made, I go about tidying it up so that anyone

else trained in Benesh can read and understand it. In fact, at that

time, 1966-1969, I had been teaching it to the Met ballet mistress,

Audrey Keane and some of the dancers as well.

After

this rough copy is made, I go about tidying it up so that anyone

else trained in Benesh can read and understand it. In fact, at that

time, 1966-1969, I had been teaching it to the Met ballet mistress,

Audrey Keane and some of the dancers as well.