CHAPTER 18

Tucson Civic Ballet

Comes To An End

It was soon time

for a return to my beloved Tucson for another spring production...

When I called for negotiations, in stunned

surprise I was presented with a sobering picture. While I was away

in New York, another dancer whom I had hired to dance and had

entrusted to rehearse the company in my absence, made it known to

the Board of Directors that he himself wanted to run the company.

Because he now had a school in Tucson, which largely through my help

and through his association with the company had supplied some

dancers, he was able to create a rallying-point. The Board

foolishly agreed. After all, they felt, why bring someone all the

way from New York when they had someone already in Tucson who could

do the job.

The Board consisted mainly of mothers, who

didn’t know much about ballet except that their daughters were in

it, and even less about choreography. They didn’t know for example,

that to be able to stage an authentic Swan Lake or Coppelia, took a

certain degree of know-how. In those days there were no videos of

these ballets that one could study and re-construct from. I did it

through Benesh notation and also having danced in them. My

replacement had none of these advantages. But he did have an imposing

figure and an ability to schmooz.

By hiring him to dance in Swan Lake, Coppelia

and Nutcracker, I had not completely thought it through. This

working at cross-purposes had a cost I should have taken into

account. How nice to be able to walk into an already built and

promising company and take it over. It was sabotage!

So I was no longer at Harkness, and now, after

seven years of building a company from scratch, I no longer had

Tucson. The bitter irony was that the Tucson Civic Ballet still

owed me over $6,000 which I had invested in its future. They had not

even taken that into account. It only underscored the extent of the

damage. What happened to all the professional scenery and costumes

that I had supplied was anybody’s guess. In three years time my

replacement had not only ruined all that I had built but also lost

the company to others. Eventually, after a long series of directors

and catastrophes it became the professional “Ballet Arizona”, based

in Phoenix. At least he benefited from the association

with a dancing school that grew to be one of the biggest in Tucson.

Transitions

I

always enjoyed doing the dancing/acting roles of Drosselmeyer and

Dr. Coppelius, after the classical, Princely roles had come to a

close for me, at least on a professional level. Of course I had

danced those roles in England and in Tucson because, well, there

was no one else to do them, but I never was a true

danseur noble. I always

envied other male dancers with stature and long elegant legs.

I wouldn’t say my height was exactly a

stumbling-block, but dancers in generations before me were small,

almost midget like. But by my time, choreographers were looking more

for the tall, blond, all-American types.

I was really born to be a character dancer and

felt more at home dancing a mazurka, a polonaise, a csardas. I had

always found that the movements of folk and character dance,

fortified by classical technique, helped achieve a greater

virtuosity, even nobility. In fact, all forms of theatrical dance,

in one measure or another, achieve a higher, more perfect level of

performance with the underpinning of classic ballet. Even skating

and gymnastics benefit by it.

I had started to be increasingly aware that

someday I would have to stop dancing professionally, and as any

dancer will tell you, this is a brutal fact to come to terms with.

Luckily, being a choreologist, I no longer had to attend dance

auditions that had been such a constant part of my early life, and

the life of every dancer who wants a stage career. The vigorous

element of competition, which continues and even increases as a

dancer contends with other dancers for jobs, gets more and more

arduous as he grows older. The constant, if unspoken competition is

wearisome. And all that, just for some minor triumph, like a job in

a musical show. It wasn’t that I didn’t know from the beginning the

characteristics of a choreologist’s job. I considered myself very

fortunate to be able to do it. Still, I was walking through the

world when I would rather had been dancing in it. I was up against a

dilemma.

Transition is an inevitable part of every

dancer’s life. Making a decision to stop dancing, or at least to

change directions is not easy.

So, what do dancers do when they cease dancing?

Teach? Choreograph? Or go into something completely different. I had

choreology. I could notate and do staging from notation, either from

my own or from that of someone else. And I could choreograph. This

could be my longevity strategy.

The Dance Notation Bureau

And Labanotation

The Dance Notation Bureau in New York seemed like a

good place to work. At least for a while. Although they promoted the

Labanotation system, which is completely different from Benesh, they

had just received a

grant from the National Endowment For The Arts

to be able to also offer the services of a Benesh choreologist. In

doing that, choreographers would be given a choice as to which

system they wanted their works to be recorded in. It only seemed

fair. grant from the National Endowment For The Arts

to be able to also offer the services of a Benesh choreologist. In

doing that, choreographers would be given a choice as to which

system they wanted their works to be recorded in. It only seemed

fair.

Unlike the attitude back at the London

Institute, the Dance Notation Bureau was far more friendly to other

systems. At least they were willing to look at them. Labanotation is

a scrupulous system of symbols developed by Rudolph Von Laban, and

like Benesh, charts every movement on paper, effectively creating a

movement ‘score’. The Labanotation of Eugene Loring's "Billy the

Kid" in 1942, was the first ballet notated in the United States. It

came at the request of the choreographer, who wanted it to help

establish his ownership of the choreography.

While working at the

Dance Notation Bureau I

became a Certified Labanotation re-constructor. That meant I was now

bi-lingual, knowing two notation systems, and this was a unique

position to hold.

During my time at the Dance Notation Bureau I was sent to

Philadelphia to notate one of Ben Harkavy’s ballets, a ridiculous

work with impossible music. Harkavy was arrogant and rude and I

remembered him in the same classes at George Chaffee’s studio when I

first arrived in New York. His name then was Benjamin Goldfarb.

A more pleasant association was when I was sent

to Hartford, Connecticut to notate Balanchine’s “Allegro Brillante”

being set by Sarah Leland. That company was then run by Michael

Utoff.

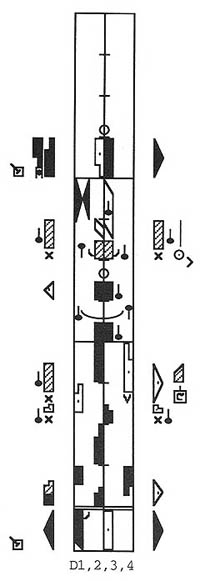

Left: Excerpt from the Labanotated score of

Balanchine’s Symphonie Concertante

American Ballet Theater

American Ballet Theater was, and is the leading ballet company in

America. It was where all the real ballet stars were in what was

termed “the golden years”.

ABT is still the best company in America, with superb dancers and a

fantastic repertory. They had used choreology before, but only with

a guest choreologist coming from England now and then to stage a

work of Ashton, or Cranko. To be a resident choreologist for ABT

would be a hard nut to crack.

As luck would have it, John Neumeier was choreographing his ‘Hamlet’

for ABT and phoned the Dance Notation Bureau for a Benesh

choreologist. I of course was the one to be sent.

Neumeier, a brilliant young choreographer, gave Hamlet a modern,

dramatic framework and he had some of ABT’s hottest stars to dance

it. Misha Baryshnikov, Eric Bruhn, Gelsey Kirkland. This was full

star quality.

For a month I sat in on every rehearsal, busily notating this ballet

with an impossible piano score by Aaron Copland. His ballet scores

for “Rodeo” and “Billy The Kid” are real Americana and certainly

danceable, but this “Connotations For Piano” was not only difficult

to listen to, it was nearly impossible to count. After one

performance, ABT pulled Hamlet from the repertory and Neumeier

returned to Germany, nearly broken hearted. I felt sorry for him,

but it really was an awful ballet. Later on he revised it for his

own company in Hamburg, Germany, using my notated score as an aid. I

hope it fared better there. For a month I sat in on every rehearsal, busily notating this ballet

with an impossible piano score by Aaron Copland. His ballet scores

for “Rodeo” and “Billy The Kid” are real Americana and certainly

danceable, but this “Connotations For Piano” was not only difficult

to listen to, it was nearly impossible to count. After one

performance, ABT pulled Hamlet from the repertory and Neumeier

returned to Germany, nearly broken hearted. I felt sorry for him,

but it really was an awful ballet. Later on he revised it for his

own company in Hamburg, Germany, using my notated score as an aid. I

hope it fared better there.

Photo: John Neumeier

All was not lost. Apparently the manager of ABT was pleased with my

work and I was called in to sign a contract as resident

choreologist. I would first be assisting the famous new defector

from the Soviet Union, Misha Baryshnikov on his first effort at

choreography, “The Nutcracker”. The Nut had finally been cracked!

|

|

|

|

Copyright ©2006-2021 OKAY Multimedia |

|

|