CHAPTER 20

American Ballet Theatre

Even with

the failure of the disastrous Hamlet with its star cast, ABT must

have been well pleased with the work I’d done while there because I

was offered an extended contract. It is never easy to establish

yourself as a choreologist with any dance company, let alone a big,

major company such as ABT. For one thing, Choreology and

Labanotation in America are not all that well known. Previously,

dancers always relied on memory in revising ballets, that is, until

the choreologists came along. I should say here that ballet masters

and rehearsal directors have been known to resent a choreologist on

staff, I suppose considering notation a possible threat to their own

job. After all, an entire ballet written down in detail is a

distinct advantage over someone who often has only a vague memory of

the work, and the more useful choreologists make themselves, the

greater the danger.

Now, in the

present age of video and computer technology, is notation then

obsolete, dying or already dead? As I am writing here mainly about

notation as a profession in America I would have to say a complex

yes, but in Europe it’s a different story. Unlike in this country,

Governments there, and elsewhere, are not shy or stingy about

funding the arts. Simply put, American dance companies as a rule

can’t afford the luxury of a full-time notator on staff. If they

want to add to their repertory a ballet by a leading choreographer,

say from Europe, a choreologist most likely is sent over to stage

it, and yes, from a notation score. Choreologists attach themselves

to certain choreographers, becoming familiar with their style and

working methods as well as full details of the actual steps and

staging.

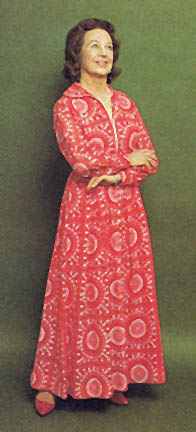

American

Ballet Theatre, known originally as Ballet Theater, was founded by

Lucia Chase in 1940. Fabulously wealthy, she poured millions into

bringing together the greatest names in ballet and establishing the

company as world class, although it remained always on the brink of

bankruptcy. She was committed to preserving the great masterpieces

of classic ballet as well as nurturing the emerging modern American

choreographers, thereby ensuring a healthy dance legacy for future

generations. American

Ballet Theatre, known originally as Ballet Theater, was founded by

Lucia Chase in 1940. Fabulously wealthy, she poured millions into

bringing together the greatest names in ballet and establishing the

company as world class, although it remained always on the brink of

bankruptcy. She was committed to preserving the great masterpieces

of classic ballet as well as nurturing the emerging modern American

choreographers, thereby ensuring a healthy dance legacy for future

generations.

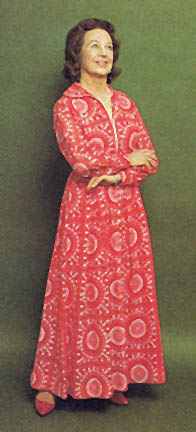

Photo: Lucia Chase

Unlike

Rebekah Harkness, hers was not a fleeting interest in ballet,

playing the patroness to young choreographers of advanced ideas but

mediocre ability. Lucia Chase was energetic, executive.

I went

immediately to their nifty offices on Seventh Avenue to sign the

contract. The studios at that time were located on two top floors of

a building on West Sixty-Third Street, just off Columbus Circle. It

had a rabbit warren of studios where the company, while not on tour,

rehearsed all day long. In the evenings, the ABT School took over

the studios. Surprisingly, I found still teaching there one of my

very first teachers from twenty-five years earlier in ABTs original,

tiny studio on West Fifty-Sixth Street; Valentina Pereyaslavic, with

her accompanist, Valya Vishnevskaya.

The

ABT company ballet masters were Enrique Martinez, Michael Lland,

Scott Douglas, and Jurgen Schnieder. Terry Orr, a principal dancer

was also given the responsibility to rehearse certain ballets. The

ABT company ballet masters were Enrique Martinez, Michael Lland,

Scott Douglas, and Jurgen Schnieder. Terry Orr, a principal dancer

was also given the responsibility to rehearse certain ballets.

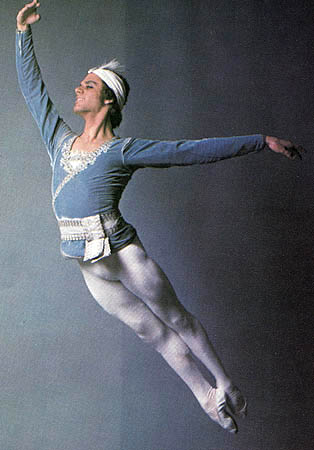

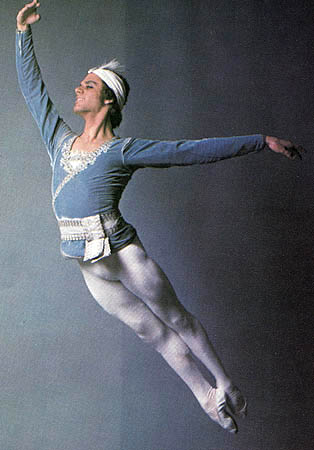

The ABT

stars, besides “Misha” Baryshnikov, were other Soviet defectors,

Natasha Makarova and Sasha Mintz. Then there was the American Prima

Ballerina, Cynthia Gregory, the Dutch Martine Van Hammel, the

ever-reliable Eleanor D’Antuono, originally from Boston, Gelsey

Kirkland, ballet’s “bad girl” whose drug dependence nearly ruined

her career, the charming Hungarian, Ivan Nage, and the fantastic

danseur noble, Fernando Bujones - no other American ballet company

could boast such luminaries.

Photo: Natalia Makarova

On my first

day I was placed in a baptism of fire. I no sooner arrived, than

Martinez had me accompany him to a rehearsal of the vision scene in

“Sleeping Beauty”. After five minutes he vanished, leaving me to

carry on to rehearse twenty-four ballerinas who didn’t even know who

I was. Fortunately, I had just finished staging a Sleeping Beauty in

Pennsylvania so knew this scene well.

Afterwards,

in the lobby, I ran into Nina, a friend of mine who knew practically

everyone in the ballet world. She was Mexican but spoke perfect

Russian and through her, I had met most of the Bolshoi Ballet people

when they were in town.

“Pozdravlyayou” she said in Russian [congratulations]. This was

because we often had talked about how great it would be if I could

be a part of ABT, which to us both seemed so unlikely.

Baryshikov’s Nutcracker

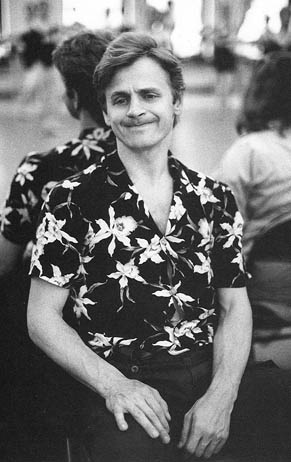

Baryshnikov was starting to choreograph a new “Nutcracker”. Being

his first effort at choreography he was, understandably, a bit

nervous and he searched for help from every direction.

We

of course knew each other from the earlier episode with Neumeier’s

“Hamlet”. Misha had been sort of chummy with me then, but as he

became more and more famous, his attitude gradually changed to, I

would have to say, arrogance. His arrogance stretched to mostly

everyone else as well. Like Rudolph Nureyev before him, his fame had

spread far beyond just a ballet audience to full media attention and

National recognition. Never shy, he had no trouble in learning the

American ways fast, and the inside politics of ballet companies. We

of course knew each other from the earlier episode with Neumeier’s

“Hamlet”. Misha had been sort of chummy with me then, but as he

became more and more famous, his attitude gradually changed to, I

would have to say, arrogance. His arrogance stretched to mostly

everyone else as well. Like Rudolph Nureyev before him, his fame had

spread far beyond just a ballet audience to full media attention and

National recognition. Never shy, he had no trouble in learning the

American ways fast, and the inside politics of ballet companies.

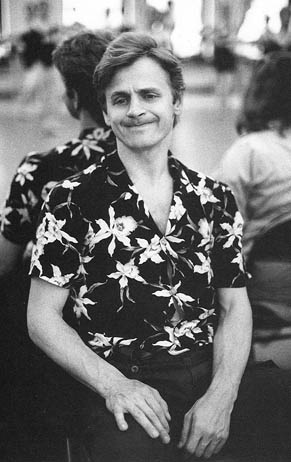

Photo: Misha directs a rehearsal

This ‘troika’

of defectors: Misha, Sasha and Natasha, stayed mostly together,

discussing how they should do Nutcracker. Jurgen Schneider also, who

although German, gained his training along with them in Leningrad.

That circle was closed to me, but during their discussions they

didn’t know that I was Russian speaking and understood mostly

everything they said, which was not very complimentary about ABT and

many of its staff.

Nutcracker

rehearsals were my main concern then, and getting it all notated.

But of course as resident choreologist, there were other rehearsals

to attend to.

Sir Robert Helpmann

Sir Robert Helpmann arrived to re-stage a “Sleeping Beauty”. He had

been one of the most famous of British male dancers from the 30s and

40s. He was also a movie dancer/actor starring in many films, such

as

1948

ground-breaking “The Red Shoes” and “Tales Of Hoffman”. Strictly as

an actor he had acted with Katherine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Charlton

Heston, and many other Hollywood stars. He was actually working in

two movies at the time and would often tell me he was off to have

lunch with Katherine Hepburn or some other notable movie queen. 1948

ground-breaking “The Red Shoes” and “Tales Of Hoffman”. Strictly as

an actor he had acted with Katherine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Charlton

Heston, and many other Hollywood stars. He was actually working in

two movies at the time and would often tell me he was off to have

lunch with Katherine Hepburn or some other notable movie queen.

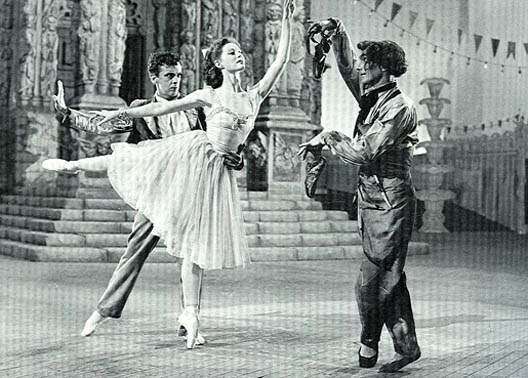

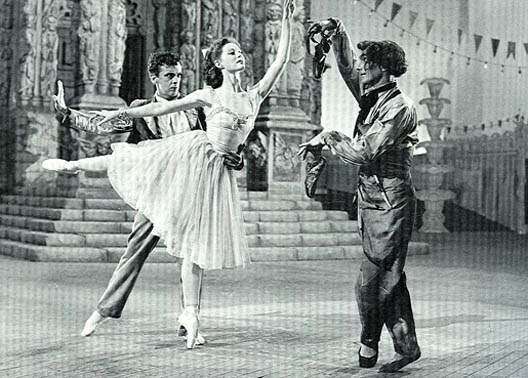

Photo: Sir Robert Helpmann in the

1948 British film "The Red Shoes" with Moira Shearer and Leonide

Massine.

We became good friends, not only because I, having spent so many

years in England, understood the British customs and manners, but

because of my ready and eager desire to help.

From the

beginning it became clear that he had little knowledge of the actual

choreography for Sleeping Beauty. He began to flounder and hesitate.

He remembered almost nothing of the steps, although he had danced it

countless times with England’s great Prima Ballerina, Margot Fonteyn.

Like my previous experience with “The Dream, he seemed, like Sir

John Hart, overjoyed at having a ready source of knowledge and made

continuous use of it, although he did have a wonderful understanding

of dramatic values and theater sense.

The dancers

had already been doing a version set by Mary Skeaping, so it was

just a matter of adjusting it here and there. Skeaping had left some

very odd ideas in her staging. Helpmann thought the Skeaping version

was rubbish, and said so to ABT officials. I loved his humorous

comments, so English. Like when at the dress rehearsal, the Lilac

Fairy made her exit in a device that was pulled up into the flies.

He whispered to me, “I asked for a basket and they built me the

Queen Mary”!

He was

somewhere in his eighties, with a mass of white hair and those

famous, bulging eyes. My suggestions took immediate hold of him and

I came to be constantly at his side as he more and more began to

rely on me. I could see he knew only some of the obvious bits, but

rather than completely taking over I merely would hint or suggest.

Sitting beside

him during rehearsals, every few minutes I would have to, tactfully,

lean over and say something like: “Shouldn’t they be doing

mazurka step here? Then he would slap his knee and say something

like: “I KNEW there was something wrong” - even though it had

completely escaped his notice.

The six fairy

variations were all wrong the way Skeaping had set them. To correct

them and other sections, I used a score from the Royal Ballet. It

became my bible and so dog-eared after two months of use, it was

barely readable.

Glenn Tetley’s “Sacre du Primtemps”

We were also rehearsing Glenn Tetley’s version of “Sacre du

Printemps”. The score I had to work with was written by another

choreologist and it was in most part, incomprehensible. Instead of

being notated straight through as it was danced, it was more like;

‘go back to section B’ or ‘repeat section D to F’ etc. so it was

cumbersome and time consuming just trying to read and locate

sections when it should have been straight on. Fortunately, Scott

Douglas, who had been one of ABTs top dancers, was an expert

repetiteur and remembered the ballet nearly step by step.

Being so involved with “Beauty” left me little time for Misha’s

“Nutcracker” but I somehow managed to attend all those rehearsals as

well notating it as carefully and as quickly as I could. Misha too

seemed to at times rely on me, even one day inviting me to join in

with the boys as they were learning a dance. It was a stressful

time. I would put in a full day at the studios, only to arrive home

to work some more on the scores before I forgot what my rapid notes

made during the day meant.

Misha’s Nutcracker A Success

“Nutcracker” opened in Washington, DC at the Kennedy Center. I

stayed with the dancers at the “Hotel Intrigue” across the street

from Watergate. The same as with the Harkness Ballet, company

officials never knew exactly where to book the choreologist - with

the staff or with the dancers. It should be with the staff, but I

didn’t mind at all being shoved along with the corps dancers. It was

a season of intense winter cold in Washington. Out of my window I

could look at Watergate and the Kennedy Center, covered with snow.

Jimmy McWhorter, who was my assistant back in the early days with

Tucson Civic Ballet, was living in Falls Church, Virginia, just

across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. He was by then married with

2 young children. Being a cellist in the Air Force orchestra, he

often played at the White House. I spent an afternoon showing him

and his family around backstage at Kennedy Center.

As is the

case while touring with ballet companies, only the hotel and theater

are seen.

Misha’s new

Nutcracker was a big success, partly because he himself danced the

leading role, although, in my opinion, Fernando Bujones was a more

elegant dancer but did not have the star appeal. Soviet defectors

were almost always guaranteed to be the reigning stars, even if

there were others who surpassed them in dance technique.

ABT’s Star Power

Rebecca Wright showed up from Joffrey Dream. A dancer with

remarkable precision and power. She always danced full out with

impeccable footwork, clearly shaped port de bras and infallible

musicality. She died in 2005 at age 58 after a prolonged battle with

cancer.

Eric Bruhn, a true gentleman in every sense and the perfect

male dancer. He later became director of the National Ballet

of Canada and died in 1987 of lung cancer. I do remember him

smoking a lot.

Ivan

Nage, a sense of wit and humor, always playing jokes. Once,

during a performance of “Les Sylphides” in which he danced

the leading male role of the poet, I happened to be standing

in the wings downstage left, as I usually did. Just as he

was making his entrance in the coda, he suddenly grabbed my

hand to pull me onstage along with him. I think he actually

would have if I hadn’t resisted with full force.

Photo: Ivan Nage |

| |

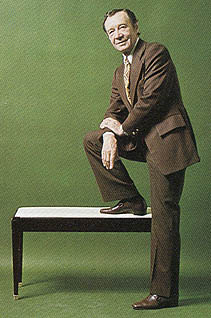

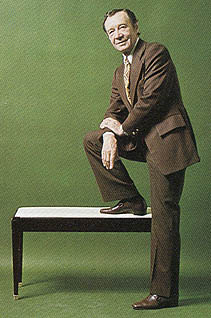

Makarova

- always pounding her point shoes and holding up rehearsals! While

rehearsing her in the role of Aurora in Sleeping Beauty I made a

horrible faux pas by showing her the way I’d remembered Margot

Fonteyn dancing it. It looked like I was comparing, which is never

done with prima ballerinas and certainly not one of Makarova’s

stature. I thought I would be fired after that but ballet master

Michael Lland told me she had probably forgotten it instantly. Makarova

- always pounding her point shoes and holding up rehearsals! While

rehearsing her in the role of Aurora in Sleeping Beauty I made a

horrible faux pas by showing her the way I’d remembered Margot

Fonteyn dancing it. It looked like I was comparing, which is never

done with prima ballerinas and certainly not one of Makarova’s

stature. I thought I would be fired after that but ballet master

Michael Lland told me she had probably forgotten it instantly.

Photo: Michael Lland, Ballet

Master

Natasha was always accompanied by Dina Makarova, same name but not

related. It was interesting overhearing them always gossiping and

complaining in Russian, not knowing that I understood.

Fernando

Bujones, always the gentleman, with impeccable technique and the

ideal classical male dancer. Tall and slim, he was one of the few

who could partner Cynthia Gregory, who always, due to her height,

had the problem of finding a suitable partner. He died from melanoma in 2005 at

the age of fifty. A great loss.

Photo Left: Fernando Bujones

Photo Right: Cynthia Gregory

|

|

Cynthia had

actually retired but made a come-back at the same time I joined.

Gelsey

Kirkland, a lithe and exquisite dancer. She was going through a

serious drug problem at the time, which she wrote about extensively

in her book “Dancing On My Grave”. She was also then having a

romance with Misha, quite obvious to us all. Gelsey

Kirkland, a lithe and exquisite dancer. She was going through a

serious drug problem at the time, which she wrote about extensively

in her book “Dancing On My Grave”. She was also then having a

romance with Misha, quite obvious to us all.

Photo: Gelsey Kirkland

And Baryshnikov. Aloof and with a shimmering bravura technique.

Obviously the show was his from start to finish.

Returning to New York there was a full month of just “Coppelia” at

the City Center. It was a tiresome version by Enrique Martinez but

came to life with Gregory and Makarova.

Firebird And Petrushka

The ABT Spring season, from April through June began at the Met. The

two new productions that interested me most were “Firebird” and “Petrushka”.

Choreologist

Christopher Newton from Royal Ballet arrived to set “Firebird”.

Another

choreologist, and a congenial one. He was perhaps the only other

choreologist I ever found to be truly friendly. Few of the others

had ever shared or given me any kind of real support.

The Fokine

version of “Firebird” is nearly an hour in length. After Christopher

left I had to rehearse it myself from the score that he left in my

hands, which was from the Royal Ballet. The Royal is a much bigger

company than ABT, and therefore corps parts had to be reduced for

the smaller ABT corps. Not as easy as it sounds.

“Petrushka”

was not exactly new. It was one of the last ballets it’s

choreographer Mikhail Fokine himself

had

set on ABT before he died in 1942. Dimitri Romanov, long-time ballet

master at ABT had danced in it at that time. As with most Russians,

I got on well with him. He liked my rehearsal comments and

assistance and always was putting a word in for me to Lucia Chase. had

set on ABT before he died in 1942. Dimitri Romanov, long-time ballet

master at ABT had danced in it at that time. As with most Russians,

I got on well with him. He liked my rehearsal comments and

assistance and always was putting a word in for me to Lucia Chase.

Photo: Dimitri Romanov, Regesseur

Watching both

of these Diaghilev ballets from the wings was always thrilling, to

me at least - the dancers thought them boring. All my "virtual"

Russian blood would surge each time I watched the wedding finale of

Firebird, with the boyars, dressed in fantastic costumes marching

upstage to the glorious Stravinsky chorale.

Backstage at

each performance, I studied every detail of the Petrushka sets; the

merry-go-round, the way the puppet theater was put together, the

mechanism of how the snow fell, thinking that one day I may even

produce it myself.

It’s always interesting for me to observe dancer’s behavior when out

of view. For instance, audiences would be shocked to see backstage

when a dancer bounds into the wings at the end of a difficult and

exhausting variation and bends over in physical agony, gasping for

breath. Not the picture to take home. Ballet dancers, both male and

female, must have strength and endurance far exceeding most sports

athletes.

In the Metropolitan Opera house, where I had once danced, I now had

my own office. I had apparently reached the peak of my career. For a

choreologist, ABT was just about as far as one could go in this

country. It was the top in prestige and salary. Actually, the salary

was then commensurate with that of a soloist.

When the company went out on tour, to San Francisco, to London, I

stayed behind, free to join the staff at the Dance Notation Bureau

until they returned. I used the time to tidy up my scores and

involve myself in life at the Bureau. I used the time to complete

from my notes the scores of Coppelia, Les Patineurs, La Bayadère, La

Sylphide, Petrushka and Nutcracker.

Antony Tudor

The leading, resident choreographer at ABT was

Antony Tudor - real

name, William Cook. He was born

1908

in London of lower-middle-class. Being myself from a lower class, I

appreciated his being able to pull himself up from it. He had been

with ABT from it’s very beginning in 1940 and considering the ABT

hierarchical nature, he demanded, and got the most respect. 1908

in London of lower-middle-class. Being myself from a lower class, I

appreciated his being able to pull himself up from it. He had been

with ABT from it’s very beginning in 1940 and considering the ABT

hierarchical nature, he demanded, and got the most respect.

Describing how he happened to come from his native England to

dance and choreograph for ABT during the initial season in 1940:

"Actually my invitation was an after-thought, the directors had

first invited Frederick Ashton to join them, but when he was unable

to come, they asked me. How lucky for me Freddie couldn't make it."

He had a

reputation of being extremely difficult for anyone to work with.

Unfriendly, sarcastic, cruel. He caused so many dancers to run out

of class or rehearsal in tears.

Photo: Antony Tudor,

Choreographer Emeritus

I knew him from the early days as a student in the old Met ballet

school. It was when Ballet Theater took over the Met dancers in

1950. A classmate and I hid in the upper reaches of the immense roof

stage studio to watch as Tudor, with a stony, expressionless face,

and a smiling Lucia Chase, auditioned and eliminated the ballet

company already in residence, with the exception of one of two. The

dancers, we thought, were cruelly cast aside as unsuitable and

replaced with a new crop. Zachery Solov became the Met’s new

resident choreographer. That’s when my classes at the old Met came

to an end, as Tudor refused to let me continue on as a non-paying

student. Bronislava Nijinska at the new ABT School did, however.

The Met

Ballet School re-started in the new house in Lincoln Center but

limited to evening classes.

One afternoon, backstage, after I had danced in a matinee of “Aida”,

Tudor told me that it might be a good idea if some of the dancers

learned Benesh notation and suggested I put a notice on the studio

bulletin board announcing that I would be willing to instruct them.

I took his advice and found several who were genuinely interested.

Typically, he neglected to tell anyone else about his suggestion.

ballet mistress Audrey Keane felt, and rightly so, that I should

have first consulted her before doing this, and sent me to General

Manager Rudolf Bing’s office for a reprimand. Mr. Bing was used to

Tudor’s inconsistencies however, and all was forgiven.

Sunflowers

The Dance Notation Bureau wanted me to stage Tudor’s “Sunflowers”

for the Met Opera Ballet.

Tudor had very strong views on how his ballets should be staged and

I got the impression he did not welcome this news. Even though I had

been sent with full approval by the Bureau to do this,

reconstructions through notation at that time were still considered

to be somewhat suspicious. And after all, who was I, who had never

even danced in any of his ballets, to be qualified to take on the

job?

Backstage at the Met I cornered him in an elevator where he assumed

I was going to ask him for steps. He gave me a scornful grunt, not

unusual for Tudor’s reaction to anyone who approached him. “I

wouldn’t think of asking you for steps” I said in a cocky sort of

way. "I just wanted to get some insight from you on casting your

ballet”. His well known harshness didn’t scare me any longer

and I had begun to discover that when I had to deal with overbearing

people, their arrogance only diminished my respect for them. Sensing

that bluffs were not going to work on me, their attitude often

changed. Others in the elevator stared in disbelief at hearing me

speak so boldly and impudently to Tudor. Had I offended some subtle

etiquette by my lack of awe? On the other hand, I thought, if he is

the right kind of man, surely he will understand and brush aside a

mere lapse of convention. This happened! He beamed, and obligingly

gave me a complete cast to work with. But underneath he was forming

a sinister plot as I was later to find out.

When ABT finished the seven week season at the Met they went on tour

to Europe. I was left behind this time. But I had plenty to do with

Sunflowers. Since I had once been a member of the Met ballet, they

still considered me to be one of them and didn’t know exactly how to

accept me as their teacher. Some were a bit envious that I had gone

on to, what they might have considered better things.

After two weeks of rehearsing the dancers and with the ballet nearly

all taught, Tudor suddenly appeared at my rehearsal, un-announced.

As if on a whim, he completely changed the cast he had originally

given me! This looked as if I had done something wrong and meant I

had to start all over again teaching the already taught roles to

different dancers. In the end, the Met Ballet never did perform it.

Their dance director, Norbert Vesak had designed the costumes after

his own ideas which Tudor didn’t like and refused to allow it to be

danced. A lot of time and money wasted. Well, that was Tudor.

ABT In Turmoil

ABT was at that time going through many changes. Suddenly news came

that Baryshnikov, determined to dance for Balanchine, was leaving to

join New York City Ballet. There had been a re-shuffling of

management when the company manager, Daryl Dobson, one day walked

out of his office in a huff and never returned. Many of the dancers

were disgruntled. Then too, the first wave of the AIDS epidemic was

heart-wrenching, affecting many in dance, Broadway and Hollywood. At

any rate, I felt the time had come for a change. The hectic way in

which ballets were put together at ABT, the constant pressure and

rush. I felt I wanted to do something else on a more creative level.

After a year and

a half, Baryshnikov re-joined ABT as Company Director. Wondrous

results were expected. Instead came arbitrary firings of some of

ABT’s best dancers, along with promotions of Misha’s favorites who

were far from ready for major roles. One could reasonably assume he

was perhaps more concerned with his own career than in keeping alive

the traditions of ABT. He commissioned choreographers to do ballets

that Lucia Chase wouldn’t have given closet space to. Not until

Kevin McKenzie became director did the company begin to regain its

prestige as, rightfully, one of truly great ballet companies of the

world.

|

|

|

|

Copyright ©2006-2021 OKAY Multimedia |

|

|

Makarova

- always pounding her point shoes and holding up rehearsals! While

rehearsing her in the role of Aurora in Sleeping Beauty I made a

horrible faux pas by showing her the way I’d remembered Margot

Fonteyn dancing it. It looked like I was comparing, which is never

done with prima ballerinas and certainly not one of Makarova’s

stature. I thought I would be fired after that but ballet master

Michael Lland told me she had probably forgotten it instantly.

Makarova

- always pounding her point shoes and holding up rehearsals! While

rehearsing her in the role of Aurora in Sleeping Beauty I made a

horrible faux pas by showing her the way I’d remembered Margot

Fonteyn dancing it. It looked like I was comparing, which is never

done with prima ballerinas and certainly not one of Makarova’s

stature. I thought I would be fired after that but ballet master

Michael Lland told me she had probably forgotten it instantly.

Gelsey

Kirkland, a lithe and exquisite dancer. She was going through a

serious drug problem at the time, which she wrote about extensively

in her book “Dancing On My Grave”. She was also then having a

romance with Misha, quite obvious to us all.

Gelsey

Kirkland, a lithe and exquisite dancer. She was going through a

serious drug problem at the time, which she wrote about extensively

in her book “Dancing On My Grave”. She was also then having a

romance with Misha, quite obvious to us all. had

set on ABT before he died in 1942. Dimitri Romanov, long-time ballet

master at ABT had danced in it at that time. As with most Russians,

I got on well with him. He liked my rehearsal comments and

assistance and always was putting a word in for me to Lucia Chase.

had

set on ABT before he died in 1942. Dimitri Romanov, long-time ballet

master at ABT had danced in it at that time. As with most Russians,

I got on well with him. He liked my rehearsal comments and

assistance and always was putting a word in for me to Lucia Chase. 1908

in London of lower-middle-class. Being myself from a lower class, I

appreciated his being able to pull himself up from it. He had been

with ABT from it’s very beginning in 1940 and considering the ABT

hierarchical nature, he demanded, and got the most respect.

1908

in London of lower-middle-class. Being myself from a lower class, I

appreciated his being able to pull himself up from it. He had been

with ABT from it’s very beginning in 1940 and considering the ABT

hierarchical nature, he demanded, and got the most respect. American

Ballet Theatre, known originally as Ballet Theater, was founded by

Lucia Chase in 1940. Fabulously wealthy, she poured millions into

bringing together the greatest names in ballet and establishing the

company as world class, although it remained always on the brink of

bankruptcy. She was committed to preserving the great masterpieces

of classic ballet as well as nurturing the emerging modern American

choreographers, thereby ensuring a healthy dance legacy for future

generations.

American

Ballet Theatre, known originally as Ballet Theater, was founded by

Lucia Chase in 1940. Fabulously wealthy, she poured millions into

bringing together the greatest names in ballet and establishing the

company as world class, although it remained always on the brink of

bankruptcy. She was committed to preserving the great masterpieces

of classic ballet as well as nurturing the emerging modern American

choreographers, thereby ensuring a healthy dance legacy for future

generations.  The

ABT company ballet masters were Enrique Martinez, Michael Lland,

Scott Douglas, and Jurgen Schnieder. Terry Orr, a principal dancer

was also given the responsibility to rehearse certain ballets.

The

ABT company ballet masters were Enrique Martinez, Michael Lland,

Scott Douglas, and Jurgen Schnieder. Terry Orr, a principal dancer

was also given the responsibility to rehearse certain ballets. We

of course knew each other from the earlier episode with Neumeier’s

“Hamlet”. Misha had been sort of chummy with me then, but as he

became more and more famous, his attitude gradually changed to, I

would have to say, arrogance. His arrogance stretched to mostly

everyone else as well. Like Rudolph Nureyev before him, his fame had

spread far beyond just a ballet audience to full media attention and

National recognition. Never shy, he had no trouble in learning the

American ways fast, and the inside politics of ballet companies.

We

of course knew each other from the earlier episode with Neumeier’s

“Hamlet”. Misha had been sort of chummy with me then, but as he

became more and more famous, his attitude gradually changed to, I

would have to say, arrogance. His arrogance stretched to mostly

everyone else as well. Like Rudolph Nureyev before him, his fame had

spread far beyond just a ballet audience to full media attention and

National recognition. Never shy, he had no trouble in learning the

American ways fast, and the inside politics of ballet companies.