CHAPTER 21

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo

Growing up in Boston, The Ballet Russe was the very first ballet

company I saw.

Actually it was also the very first ballet dancing I saw, apart from

what little there was in the movies. With the legend of Nijinsky

still in my mind, what I expected was something out of this world.

Already familiar with the Rimsky-Korsakoff music for “Scheherazade”,

when the curtain opened on this celebrated ballet show-piece, what I

hoped to see would be a spectacular feast for the eye. Instead, a

major disappointment was in store. Perhaps I was still too young to

fully take it all in. When I saw it again, many years later, I was

more than dazzled by its exotic dancing and trappings.

All, however, was not lost. The other ballet on the program was

“Night Shadow” now called, “La Sonnambula”, with Alexandra Danilova

and Frederic Franklin. This one I liked or at least convinced myself

that I liked it. Nonetheless, I continued ballet lessons. What else

could I do? What other hopes could I have for some kind of a future

to take me away from a miserable home life?

Danilova and Franklin were among the top dancing stars that led this

company on its grueling tours of American cities, great and small.

For more than two decades it pioneered the appreciation of ballet

throughout the United States, becoming one of the most beloved

companies in history.

The company spent most of its time in traveling, by train, by bus.

As a rule it was only for a one-night stand, then off to the next

city. The hotel and the theater were all the dancers ever got to

see. It was a hard life, but these dancers had the advantage of

youthful exuberance and a deep love for what they were doing.

The company billed itself as “The One and Only” and it truly was.

Beginning in 1938, it flourished until 1962 when it disbanded,

unnoticed, after a final performance in Brooklyn.

When I went to audition for Ballet Russe in the very early 1950s, I

had high hopes. My first New York teacher, George Chaffee, had told

me that I was ready for it

At the audition, Frederic Franklin and the company’s ballet master

Michel Katcharoff sat and watched us hopefuls. All dance auditions

in New York were filled with young hopefuls. When my turn came it

was with another boy.

Both of us went through the given combinations of steps but I

noticed they seemed more interested in the other boy. Why, I asked

myself, did I have to end up competing with someone taller, more

handsome, more all-American looking?

I was ignored. So, it was back to my job selling candy at the Roxy.

Michel Katcharoff

About twenty years later, during the early 1970s, Michel Katcharoff

showed up at Youskevitch’s ballet studio. The next day he was

teaching a class there. He must have been in his mid -seventies by

then and not at all sure-footed. Nervous and shaky, it could easily

be seen he had not taught for a very long time and had probably come

on hard times

During

his dancing days, he had appeared in Agnes de Mille’s “Rodeo”,

“Gaite Parisienne” “Graduation Ball” and all other Ballet Russe

favorites. Like Frederic Franklin, he also had a good eye and the

ability to see details with a phenomenal memory. When replacements

were needed he taught the new dancers their role, similar to what I

did with ABT. When he became a régisseur (ballet stage director) he took on more

responsibilities, not only to rehearse the repertory and watch over

performances, but also to serve as a supervisory stage manager.

Since there was never enough money in Ballet Russe for assistants,

he had to, for each performance on tour, see that the scenery was

hung properly, give lighting cues and mastermind curtain calls. He

even had to go to the dressing rooms and yell “places” before the

curtain went up, a task these days done by the stage manager or his

assistants. During

his dancing days, he had appeared in Agnes de Mille’s “Rodeo”,

“Gaite Parisienne” “Graduation Ball” and all other Ballet Russe

favorites. Like Frederic Franklin, he also had a good eye and the

ability to see details with a phenomenal memory. When replacements

were needed he taught the new dancers their role, similar to what I

did with ABT. When he became a régisseur (ballet stage director) he took on more

responsibilities, not only to rehearse the repertory and watch over

performances, but also to serve as a supervisory stage manager.

Since there was never enough money in Ballet Russe for assistants,

he had to, for each performance on tour, see that the scenery was

hung properly, give lighting cues and mastermind curtain calls. He

even had to go to the dressing rooms and yell “places” before the

curtain went up, a task these days done by the stage manager or his

assistants.

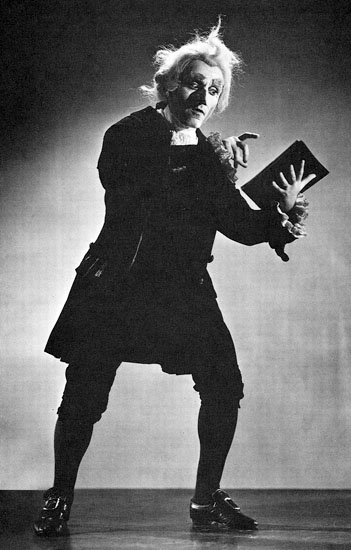

Photo: Mishel Katcharov as Doctor

Coppelus in Léo

Delibes'

Coppélia

As with most Russians, we easily became friends, although he was not

actually Russian. He was born in Iran of Armenian parents and

studied ballet in Russia from a very early age. That accounted for

his Russianization. Michel, who sometimes used Mikhail, Michael or

Misha as variants of his first name, had also taught for Dance

Congress in the past. That’s how he knew Lucille Stoddart, the very

odd lady who ran it.

It was he who introduced me to Dance Congress where I taught the

“Humpbacked Horse” and “La Bayadère” to those teachers who sat

motionless through the entire weekend while I, huffing and puffing,

danced everything myself. When some actually did come out on the

floor they could only stumble through, approximating the steps. What

they really wanted was little kiddie ballet routines to teach their

students, not quality choreography. Even so, I made good money

during those teacher conventions.

Misha, having just arrived from Europe, found a studio apartment on

West Fifty-Seventh Street and started making a come-back. His

classes got better. I told him about the time I had once auditioned

for him and Franklin but was not taken. Sympathetically, he said

that if he had known how hungry I was then, he would have taken me

in. That was most comforting to hear, after twenty years!

One day I invited him to come on over to the Met to watch me

rehearse Antony Tudor’s “Sunflowers”. The rehearsal was on “C”

level, down in the very lower depths of the opera house. I

introduced him to the ballet mistress, Audrey Keane, and some of the

dancers. After he watched for about five minutes, without a word, he

got up and swiftly left. It was amazing how, without a guide, he was

able to find his way through the maze of hallways and studios to an

elevator and up to stage level and the stage door. The next day I

called to ask why he left in such a hurry. It was easy to guess that

he felt, sadly, being no longer a part of the professional world of

ballet, found it too painful just watching. He was like that.

By then I was getting familiar with his strange attitudes.

Even so, we decided to go together to Miami Beach for a couple weeks

vacation. At the beach hotel, he was booked in a room a few floors

below mine. Every night he would terrify me with a phone call to

tearfully say he was dying. Not a very pleasant way to spend a

vacation. But during the evenings, while taking long walks along the

beach, he would tell me stories about his youth in Moscow, about

dancing for Nijinska in Paris and the dancers of Ballet Russe. It

was interesting hearing about the hardships and scandals that went

on in the ballet companies.

No sooner back in New York, he was hospitalized as manic depressive.

His nephew, visiting from Washington, D.C. found my name and called,

asking if I would visit Misha in hospital, which I did.

Misha had many friends from the old Ballet Russe days. Apparently,

friends can’t help all that much when depression takes over. He died

in Arlington, Virginia after a fall at age 82. He had Parkinson’s

disease.

|

|

|

|

Copyright ©2006-2021 OKAY Multimedia |

|

|